Sarah Buddle

2026-01-16 00:00:00

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapies show promise for treating a variety of serious genetic conditions, including hemophilia1,2,3, muscular dystrophies4 and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)5. As of 2025, there were seven AAV gene therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration6, with many more in clinical trials. The most common adverse effect of intravenously administered AAV gene therapies is hepatotoxicity, routinely treated with high dose steroids. Occasionally, liver toxicity is severe, and some patients have experienced fulminant liver failure7,8,9,10,11. Hepatotoxicity tends to be more severe in older patients with a higher body weight, who receive higher vector doses12,13.

The mechanisms underlying hepatotoxicity are incompletely understood, and it has been postulated to be caused by innate, humoral and cellular immune responses to the vector capsid, genome or transgene product14,15,16, by impurities within the vector preparation17,18 or from a direct toxic effect19,20. Acute sinusoidal endothelial injury resembling capillary leak syndrome has also been well documented in nonhuman primates using both empty capsids and therapeutic transgenes21.

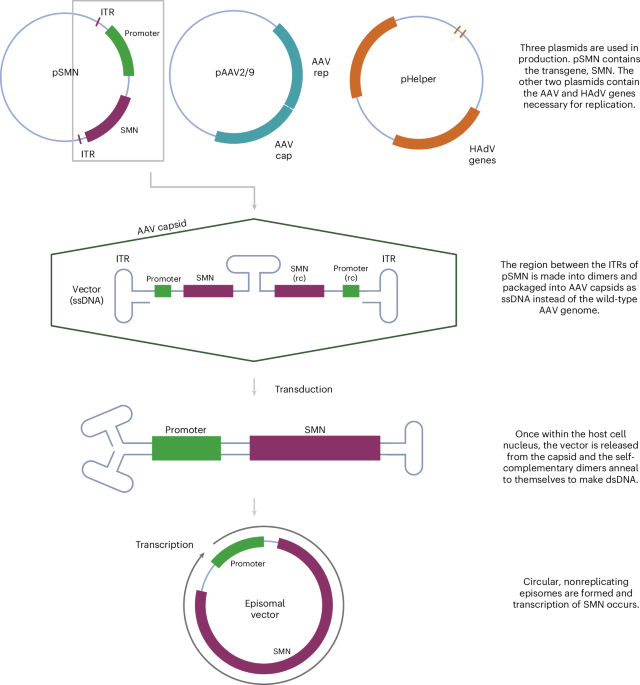

Onasemnogene abeparvovec (OA) is an AAV-vectored gene therapy for SMA, a neurodegenerative disease caused by deleterious variants in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene22. OA is manufactured using three plasmids (Fig. 1): a vector plasmid (pSMN), which contains SMN and elements necessary for its expression; a packaging plasmid (pAAV2/9), which contains AAV2 replication (rep) and AAV9 capsid (cap) genes; and a helper plasmid (pHelper), which contains adenovirus (HAdV) genes necessary for AAV replication23,24. The resultant vector preparation contains therapeutic recombinant AAV (rAAV) particles that have an outer AAV9 capsid, containing a vector genome encoding human SMN. Manufacturing process-related impurities, including empty capsids, reverse-packaged plasmids, genome fragments and recombined products, are also present in rAAV preparations, even after good manufacturing practice procedures25,26,27. These manufacturing issues are complex to study and resolve, and the US Food and Drug Administration has released guidance on reporting and validating the steps in the manufacturing process28.

OA is produced by transfection of HEK293 cells with a vector plasmid (pSMN), containing SMN between AAV ITRs, an AAV plasmid containing AAV2 rep and AAV9 cap genes (pAAV2/9), and a helper plasmid containing HAdV genes such as E2A, E4 and VA RNA genes (pHelper)23,24. SMN, survival motor neuron; HAdV, human adenovirus; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA. Created with BioRender.com.

We investigated a 7-year-old female patient treated with OA for SMA type 1 (homozygous deletion of exon 7 of SMN1, two copies of SMN2), whose clinical course has been reported previously (case 2, Finnegan et al.12). The patient weighed >20 kg at the time of infusion, and therefore required a high total vector dose of 2.2 × 1015 vector genomes. The patient experienced symptomatic hepatitis, with vomiting, jaundice, abdominal pain and dark urine. Serum hepatic markers, indicating liver injury, peaked 7 weeks after infusion (Extended Data Table 1). Liver injury was managed using steroids and tacrolimus. Tacrolimus was successfully withdrawn 7 months after infusion, and steroid treatment continued for 19 months.

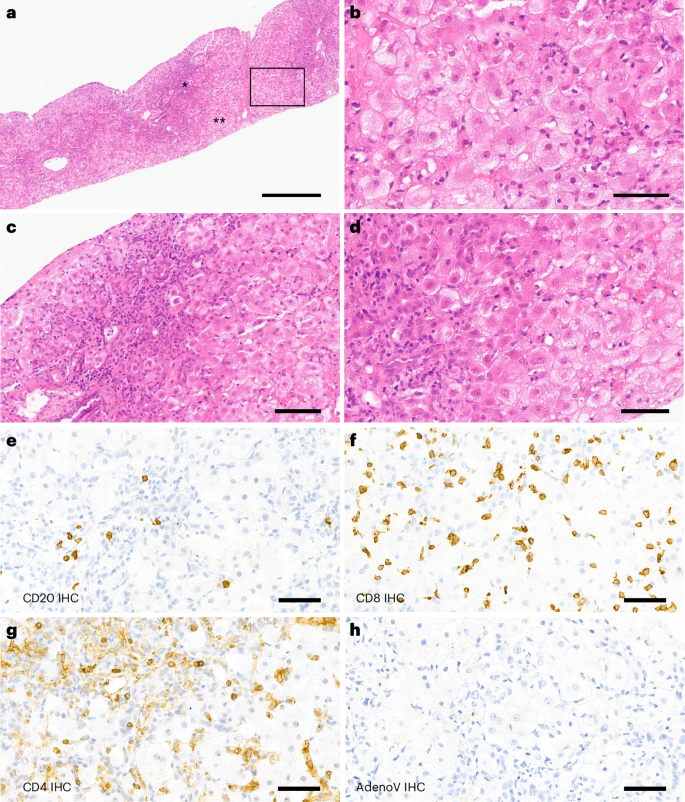

A needle core liver biopsy, taken 7 weeks after infusion, showed mild perivenular and portal fibrosis and a single focus of porto-central necrosis. There was mild portal tract expansion, including a portal ductular reaction and periductal and intraepithelial neutrophils. There was a moderate portal inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of CD4- and CD8-positive T lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells, with mild interface inflammation and moderate lobular inflammation with foci of hepatocellular cholestasis (Fig. 2). Few CD20-positive B lymphocytes were detected. These histological features are consistent with those previously reported in children with hepatitis associated with wild-type AAV2 infection29,30 and in ‘indeterminate’ pediatric acute liver failure31. Adenovirus immunostaining was negative (Fig. 2h).

a, Liver biopsy of the patient shows marked periportal and lobular inflammation as well as interface inflammation (*); numerous hepatocytes with ballooning degeneration are present (**). b, High magnification of the box in a, with ballooning hepatocytes highlighting the swollen cytoplasm. c, Magnification of the ‘*’ region from a. d, Magnification of the ‘**’ region from a. e–g, Inflammation in the liver is shown by immunohistochemistry (IHC) detecting CD20 (e), CD8 (f) and CD4 (g). There was no noteworthy steatosis or spotty necrosis, and special stains did not show periportal diastase periodic acid-schiff (DPAS)-positive globules or iron deposition. h, Adenovirus immunostaining was negative. Scale bars, 400 µm (a), 60 µm (b and d), 100 µm (c) and 50 µm (e–h). All available tissue was stained, and representative images have been captured to illustrate the signal in the sample.

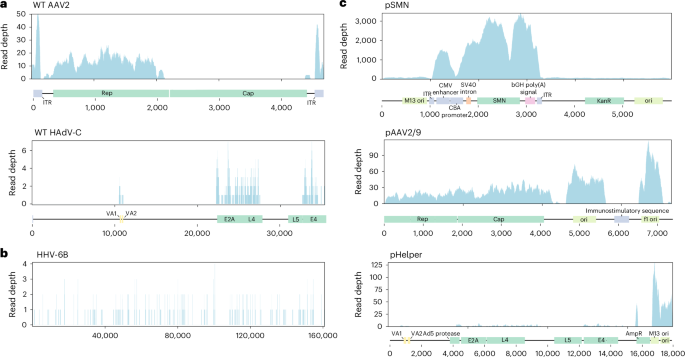

We conducted untargeted short-read metagenomic sequencing of DNA and RNA from the residual patient liver sample. In the DNA sequencing analysis, the initial assignment of nonhuman reads to the most likely microbial species identified multiple serotypes of AAV, primarily AAV2, as well as human mastadenovirus C (HAdV-C) and human betaherpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B) (Extended Data Table 2). Reads assigned to HHV-6B covered the breadth of the genome (Fig. 3b) and a specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for HHV-6B was positive (cycle threshold (CT) 26.2), indicating natural HHV-6B infection.

a, Genome coverage of wild-type (WT) AAV2 and HAdV-C from Illumina sequencing reads. Approximate locations of the genes present in the manufacturing plasmids are marked along the x axis. AAV2 alignment uses more stringent mapping parameters to more clearly differentiate between any AAV2- and AAV9-derived sequences (Methods). b, Alignment of Illumina sequencing reads to the HHV-6B genome shows reads cover the breadth of the genome. c, Alignment of Illumina sequencing reads to approximate manufacturing plasmid sequences shows the presence of plasmid sequences. CMV enhancer, cytomegalovirus enhancer; SV40 intron, simian virus 40 small intron; bGH poly(A), bovine growth hormone poly(A) signal. In the negative control, ten reads aligned to the pSMN sequence, while no reads aligned to the pAAV2/9 or pHelper sequences.

The incomplete genome coverage of AAV2 and HAdV suggested that the results did not derive from a wild-type infection (Fig. 3a). To investigate this further, we aligned the reads to the manufacturing plasmid sequences used in OA production. We found good coverage of the OA vector genome as expected, but also of the pSMN plasmid backbone and of pAAV2/9, and some reads mapping to pHelper (Fig. 3c). The reads originally classified as AAV2 or HAdV-C aligned only to sections of the viral genomes that are part of the OA manufacturing plasmids (AAV2 rep, HAdV E4, E2A, L4 and VA regions), suggesting the presence of plasmid sequences in the liver tissue rather than wild-type virus infection (Fig. 3a). A specific PCR for HAdV, targeting a region of the genome that is not present in the pHelper plasmid, was negative.

The presence of the pAAV2/9 plasmid sequences also potentially explains why multiple AAV serotypes, other than AAV2, including AAV4 and AAV8, were found in our initial classification. As there is not currently a RefSeq reference sequence for AAV9, it is not included in the metagenomics database. Therefore, reads from the AAV9-derived region in pAAV2/9 (AAV9 cap gene) were probably misclassified as other AAV serotypes in the initial analysis. We performed an alignment of reads from the liver to AAV1–9 genomes, finding the best alignment to the rep gene of AAV2 and the cap gene of AAV9 (Extended Data Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1), in keeping with the chimeric structure of pAAV2/9 (AAV2 rep gene and AAV9 cap gene). Some short regions of the pAAV2/9 plasmid sequence had no aligning reads (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the sequence we used was not fully identical to the plasmid sequence used in OA manufacture, which is proprietary. Analysis of long-read metagenomic DNA data yielded similar results: initial classification identified AAVs, HAdV and HHV-6B, but subsequent alignment revealed sequences corresponding to all three manufacturing plasmids (Extended Data Table 2).

Classification and alignment of the nonhuman RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) metagenomics data detected two reads corresponding to the AAV2 rep gene. Four further reads showed BLAST similarity to the AAV inverted terminal repeat (ITR) region but did not align. No RNA reads corresponding to pHelper, HAdV or HHV-6B were found. Previous published work has shown that our RNA-seq metagenomics protocol is as sensitive as targeted real-time PCR32. The low-level AAV RNA could result from transcription of the AAV2 rep gene; however, this signal is below the typical reporting cutoff of the metagenomics protocol and would require further validation. RNA-seq sequence alignment confirmed the presence of RNA transcripts corresponding to the OA vector genome, including SMN1 exon 7 (Extended Data Fig. 1b), suggesting successful expression of the therapeutic transgene.

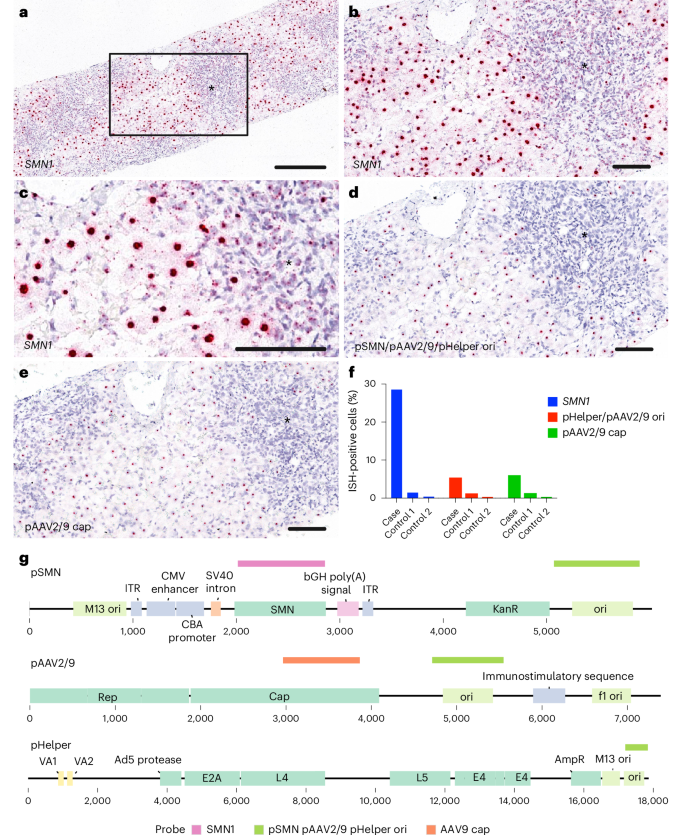

Next, we performed in situ hybridization to confirm the presence and location of nucleic acid sequences derived from OA. A probe for human SMN confirmed successful vector transduction in the patient’s liver, with 28.5% of cells in the biopsy tissue showing a positive signal (control patients showed 0.4–1.5% positive cells; Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 2). We observed both nuclear and cytoplasmic positive signals. To detect plasmid sequences, we designed probes complementary to regions of the manufacturing plasmids that are absent from both the therapeutic OA vector genome and the human genome. Analysis confirmed the presence of the bacterial origin of replication in pSMN, pHelper and pAAV2/9 plasmids in 5.1% of cells (probe vector-pHelper-C1, 0.2–1.1% positive in controls), as well as a sequence from the AAV9 cap gene present in pAAV2/9 in 5.8% of cells (probe AAV-HeB-T1-VP1-O1-C1, 0.2–1.1% positive in controls) (Fig. 4). The contaminant plasmid-specific sequences were found at lower levels than SMN, in agreement with the metagenomic sequencing.

a–c, In situ hybridization (ISH) for the detection of SMN1 in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) liver tissue. a, A strong positive red signal was detected in the nucleus of ballooning hepatocytes separated by areas with severe immune cell infiltration (*). The box in a is magnified in b. b, Higher magnification of SMN1-positive hepatocytes next to the immune cell infiltrate (*). c, Dense nuclear signal for SMN1 and a mild-to-moderate, punctuated signal within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes and immune cells (*). d,e, ISH for the detection of manufacturing plasmid sequences in FFPE liver tissue: pSMN/pAAV2/9/pHelper ori (d) and pAAV2/9 cap (e). f, The percentage of positive cells versus two control liver tissues (control 1, explant liver tissue from a child affected by severe hepatitis in AAV2 outbreak; control 2, healthy adult liver). g, Schematic showing probe binding sites on manufacturing plasmid sequences. See Extended Data Fig. 2 for controls. Scale bars, 300 µm (a) and 100 µm (b–e). All available tissue was stained, and representative images have been captured to illustrate the signal in the sample.

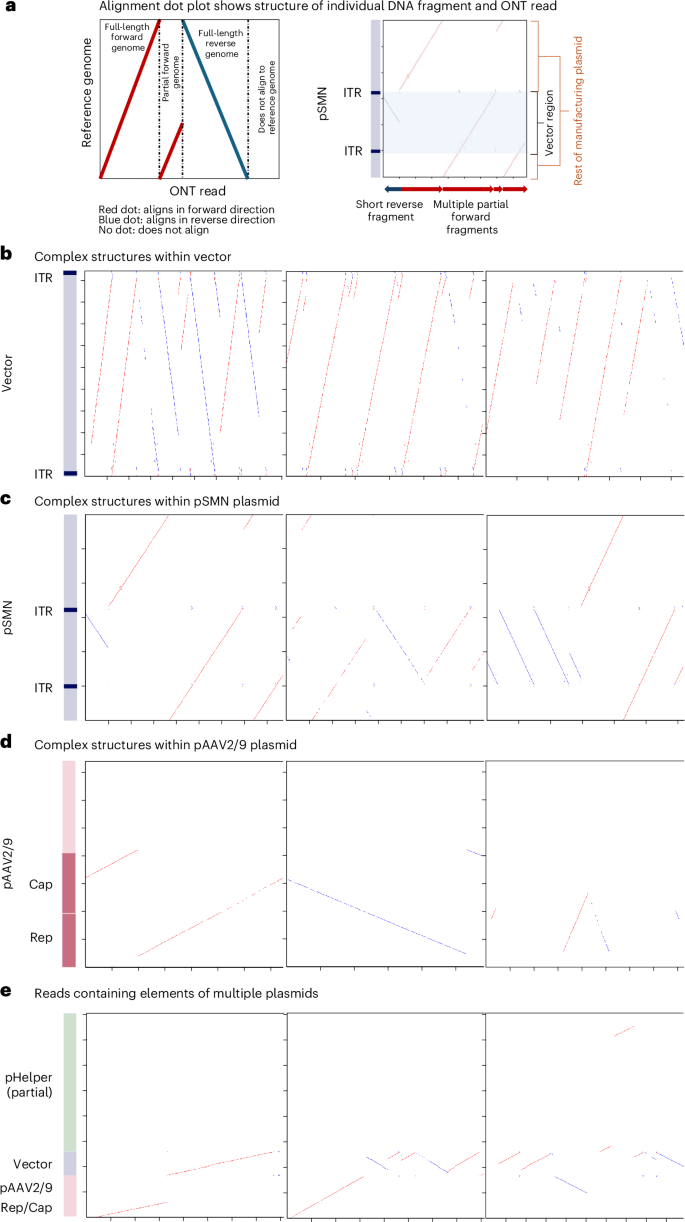

We undertook detailed sequence analysis of individual reads from the long-read sequencing to determine the vector genome structures present in the liver. This showed high levels of vector genome concatemerization and complex genome structures with rearrangements (Fig. 5a–d and Extended Data Table 3). The concatemeric patterns observed, including head-to-head, head-to-tail and alternating repeats, showed similarities to those seen in replicating AAVs using rolling hairpin and rolling circle amplification33. Plasmid reads tended to not represent full-length plasmids but rather fragments of plasmid sequences in combination with the vector genome. The majority of pAAV2/9 reads also contained regions of the other manufacturing plasmids, indicating recombination between plasmids (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Table 3). Most of the complex structures and recombination events involved the vector genome, the rep–cap region of pAAV2/9 and the region of pHelper containing the HAdV-derived genes (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Table 3).

Alignment dot plots showing individual nanopore reads (x axis) aligning to representative sequences of the OA manufacturing plasmids (y axis). Red dots indicate alignment to the forward strand, and blue dots indicate alignment to the reverse strand. a, Explanation of dot plot format. b, Alignment against the vector region of the pSMN plasmid. c, Alignment against the entire pSMN plasmid. d, Alignment to the pAAV2/9 plasmid. e, Alignment to regions of all three plasmids—the vector region of pSMN, AAV rep and cap within pAAV2/9 and the HAdV gene region within pHelper. Representative images were selected; the number of reads in each category can be found in Extended Data Table 3, and diagrams for all reads are provided in the Supplementary Information. See the Supplementary Information and Methods for description of similar dot plots generated for human reads.

Rearranged sequences may derive from recombined plasmid contaminants outside vector particles, mispackaged recombined DNA from manufacture and/or recombination events after infusion. Many of the structures we observed were longer than the maximum packaging length of an AAV vector (up to 15 kb, while the packaging limit is approximately 5 kb (refs. 34,35)). Purification steps during manufacture are designed to remove nonpackaged DNA, and efficiency of uptake of any remaining DNA is likely to be low, suggesting that some recombination may have occurred in vivo, as previously described in nonhuman primate liver36.

We also identified numerous internal vector rearrangements at the DNA level from the short-read metagenomics. First, chimeric reads were identified, signifying read-through transcripts and noncanonical splice fusions at both DNA and RNA levels (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Mapping the reads to the vector plasmids revealed that most occurred between the AAV2 ITRs, with further junction points identified between the plasmid backbone and SMN transgene (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Without direct sequencing of the vector batch, we could not determine whether these rearrangements occurred during vector manufacture or within target cells, as investigated in previous studies36. Analysis of corresponding RNA reads showed substantially fewer chimeric transcripts, suggesting these rearranged DNA sequences generally did not produce stable transcripts (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Our study also revealed potential integration of AAV into the host genome. Analysis of chimeric DNA reads mapped to the pSMN plasmid revealed numerous vector–human junctions throughout the vector genome, including a small number of junctions in the plasmid backbone (Extended Data Fig. 4). However, only a subset of these junctions appeared in chimeric RNA reads (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Notably, we detected several chimeric RNA reads in the hybrid cytomegalovirus enhancer/chicken β-actin (CBA) promoter region. Analysis of the human portions of chimeric reads mapped to the human reference genome revealed no specific fusion hotspots at either DNA or RNA levels. Chimeric DNA reads predominantly localized within gene bodies, as determined by their positions relative to annotated gene loci (Supplementary Table 3). Chimeric RNA reads were detected at lower frequencies, also primarily within transcribed gene bodies without any discernible hotspots (Supplementary Table 4).

Random, low-frequency integration of rAAV vectors in patient tissue is now well recognized37,38,39,40, and AAV integrants in complex concatemers containing mixtures of rearranged and truncated vector genomes have been demonstrated in the liver tissue of nonhuman primates after intravenous administration of rAAV8 vectors36. Chimeric reads containing plasmid sequences and non-SMN human DNA were also identified by the long-read sequencing, but due to the use of a ligation library preparation kit, we were unable to verify that these were not sequencing artifacts. AAV vectors are expected to persist episomally in postmitotic cells, and therefore it is plausible that vectors and associated contaminating sequences are maintained even without integration.

In conclusion, our metagenomic sequencing approaches, together with in situ hybridization, provide evidence that sequences from all three manufacturing plasmids were present in the liver of a patient with severe hepatitis after treatment with OA, 7 weeks after infusion. Long-read sequencing also revealed extensive disruption and concatemerization of vector genomes and manufacturing plasmids, with evidence of recombination events. Complex structural rearrangements and concatemers of AAV vector genomes have previously been demonstrated in macaque liver after treatment with rAAVs36,41 and in human hepatocytes in a humanized mouse model42. Similar complex concatemeric structures have also been noted in liver samples from children with hepatitis associated with wild-type AAV2 infection29. It will be important to ascertain whether these genomic structures are also present in rAAV-treated patients without hepatitis.

The relevance of our finding of HHV-6B in the liver is unclear in this single case description. Although it is noteworthy that HHV-6 can act as a helper virus in wild-type AAV2 replication, we detected no HHV-6 RNA, suggesting no active viral replication at the time of biopsy. HHV-6 has also been found in liver tissue in a proportion of children with hepatitis associated with wild-type AAV2 infection, although also sometimes in controls29,30, and has been found in children with acute liver failure of unknown cause43,44.

The mechanism by which complex rAAV-derived genome structures are produced, and whether they arise solely during manufacture or within transduced liver cells, remains unclear. Unfortunately, we have been unable to the access the OA batch used to infuse this patient, and there is no obligation for it to be retained by the regulators. We postulate that presence of certain manufacturing plasmid sequences (such as AAV rep gene and HAdV helper regions) and/or helper viruses (such as HHV-6) could enable amplification of the vector genome within cells if expressed, giving rise to the complex concatemeric structures we observed. Formation of replication-competent rAAV particles due to nonhomologous recombination in the course of vector production has been described45. Alternatively, these large DNA concatemers may arise purely from ITR-driven intermolecular recombination of transduced rearranged vector genomes46,47.

Future work is needed to determine the frequency and pathological consequences of complex DNA structures in patient liver cells after rAAV gene therapy, whether they are episomal or integrated into the host genome, the putative role of contaminating plasmid sequences and their potential toxicity and/or immunogenicity, and how together these factors may relate to the hepatotoxicity of rAAV gene therapies. This may inform both the management of patients receiving gene therapies and the manufacture of rAAV vectors.