Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Life: Metabolomic Analysis of Fossilized Bones Reveals Diet, Disease, and Habitat of Early Animals

For decades, paleontologists have painstakingly reconstructed the lives of extinct animals thru skeletal analysis. Now, a groundbreaking new approach is adding a vibrant layer of detail to that picture, revealing insights into the diet, health, and even the environment of creatures that roamed the Earth millions of years ago. Researchers at NYU College of Dentistry, led by Dr. Timothy Bromage, who directs the Hard Tissue Research Unit, have pioneered a technique utilizing metabolomic analysis of fossilized bones – a method that’s rewriting our understanding of prehistoric life.

This isn’t simply about identifying what animals lived where; it’s about understanding how they lived, offering a window into their daily struggles, nutritional habits, and the ecosystems they inhabited.The implications for paleoecology, evolutionary biology, and even our understanding of ancient disease are profound.

The Science Behind the Breakthrough: Trapped Biomolecules in Bone

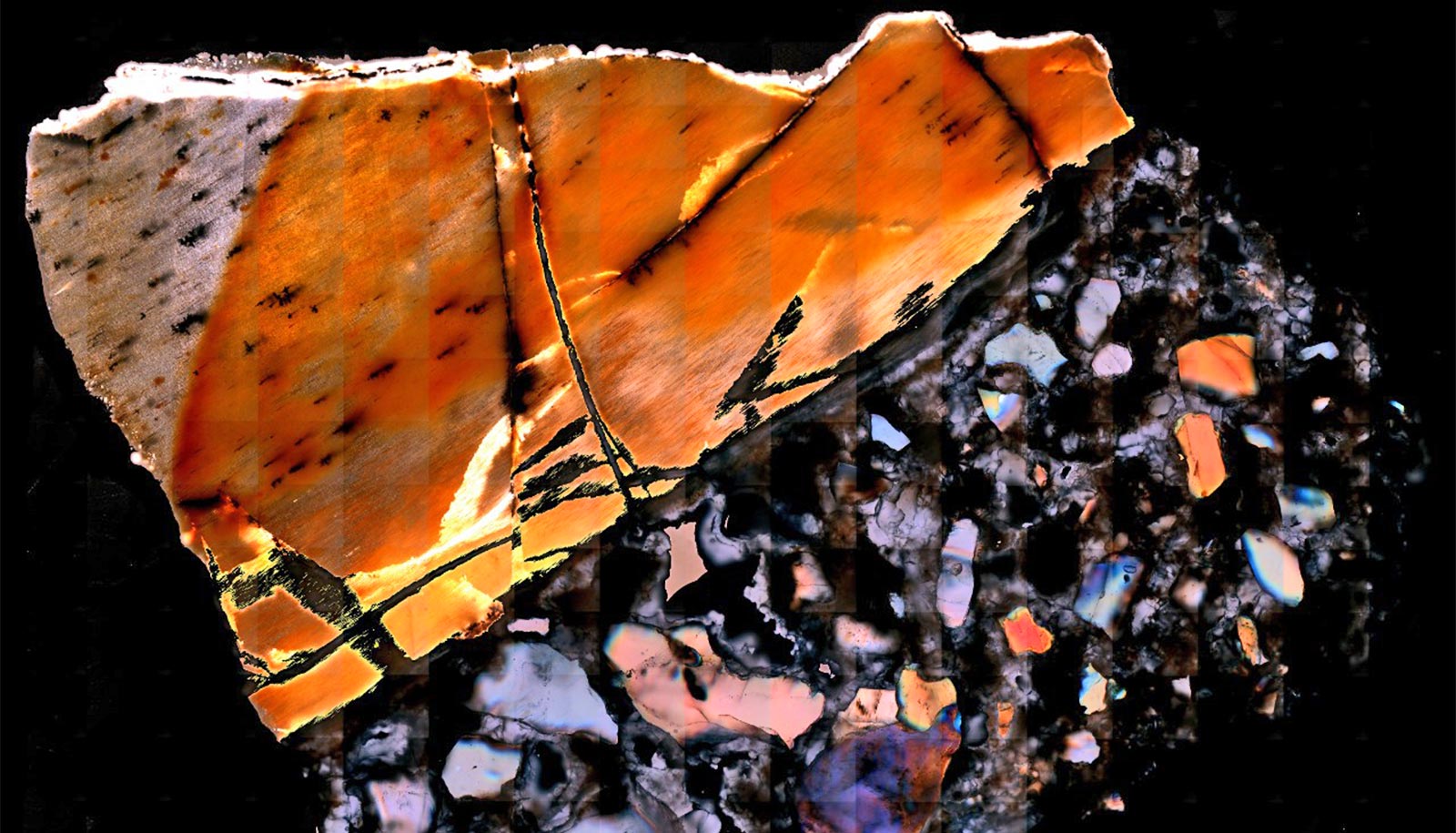

The foundation of this research rests on a engaging biological principle. Bones,while seemingly inert,are surprisingly dynamic tissues. Their surfaces are porous, interwoven with capillary networks that facilitate the exchange of vital oxygen and nutrients. Dr. Bromage hypothesized that during bone formation, metabolites - the byproducts of metabolic processes – become trapped within these microscopic niches, effectively preserving a snapshot of the animal’s internal biochemistry.

To test this theory,the team employed mass spectrometry,a powerful analytical technique that ionizes molecules,allowing for their identification and quantification. Initial tests on modern mouse bones successfully identified nearly 2,200 metabolites, alongside proteins like collagen, validating the principle of biomolecular preservation. this success paved the way for a far more ambitious undertaking: analyzing fossilized remains.

From Tanzania to germany: Analyzing Fossils Millions of Years Old

The research team meticulously analyzed bone fragments from animal fossils ranging in age from 1.3 to 3 million years old, sourced from paleontological sites in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa – regions historically inhabited by early humans. focusing on species with modern-day counterparts in these areas (rodents like mice, ground squirrels, and gerbils, as well as antelope, pig, and elephant), they applied the same rigorous metabolomic analysis.

The results were astonishing. Thousands of metabolites were identified, with significant overlap between fossilized and modern specimens. This confirmed the remarkable durability of these biomolecules and opened up a treasure trove of information.

Revealing Ancient Lives: Diet, Disease, and Gender

The metabolic signatures extracted from the fossils painted a surprisingly detailed picture of these ancient animals. Many metabolites pointed to standard biological functions - the metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals – confirming the fundamental similarities in life processes across millennia.

Though, the analysis whent far beyond the basics. Researchers detected metabolites associated with estrogen, providing clues about the sex of some individuals. More dramatically, they uncovered evidence of disease. In a 1.8-million-year-old ground squirrel from tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, the team identified a metabolite unique to Trypanosoma brucei, the parasite responsible for sleeping sickness in humans, transmitted by the tsetse fly.

“We not only found evidence of the parasite itself, but also the squirrel’s metabolomic response – an anti-inflammatory reaction to the infection,” explains Dr. Bromage. “This is a level of detail previously unimaginable from fossilized remains.”

The analysis also shed light on the animals’ diets. While plant metabolite data is less extensive than that for animal health, the researchers identified metabolites from regionally specific plants, including aloe and asparagus. This discovery allowed them to infer that the squirrel had consumed these plants, further enriching the understanding of its lifestyle.

Reconstructing Ancient Environments with Unprecedented Accuracy

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of this research is its ability to reconstruct the environments in which these animals lived. The presence of aloe metabolites, such as, provided valuable clues about temperature, rainfall, soil conditions, and vegetation cover.

“as aloe thrives in specific environmental conditions, we can infer details about the squirrel’s habitat,” Dr. Bromage explains. “We’re essentially building a story around each animal, reconstructing their world with remarkable precision.”

These reconstructed environments align with existing paleoecological data. As an example, the analysis confirmed that the Olduvai Gorge Bed in Tanzania was once a freshwater woodland and grassland, while the Upper Bed was characterized by dry woodlands and marsh. Importantly, the findings consistently indicate that these regions were wetter and warmer millions of years ago than they are today.

The Future of paleoecology: A New Era of Discovery

This research represents a paradigm shift in paleo