Leopard Attacks on Homo habilis: New AI Analysis Reveals Early Human Ancestors Were on the Menu

For decades, scientists have debated the dangers faced by our early human ancestors. Now, groundbreaking research utilizing artificial intelligence suggests Homo habilis, a key species in human evolution, was actively preyed upon by leopards around 1.85 to 1.8 million years ago. This finding, published recently, offers a chilling glimpse into the precarious lives of these early hominins and reshapes our understanding of predator-prey dynamics in prehistoric Africa.

Uncovering the Evidence at Olduvai Gorge

The study, led by Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo and his team, focused on two well-preserved H. habilis specimens unearthed from the famed Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania:

* OH 7: A juvenile individual.

* OH 65: An adult individual.

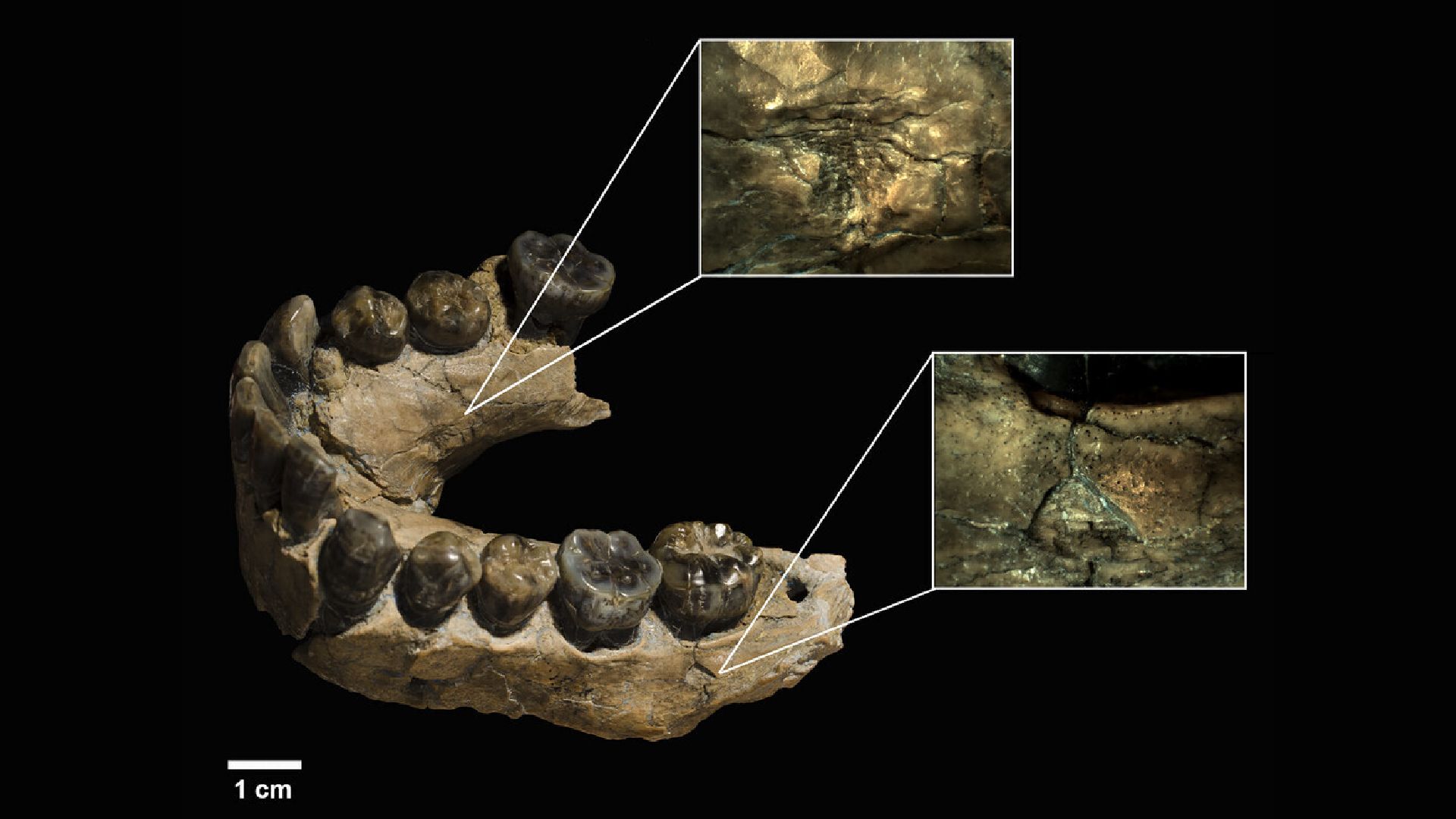

These fossils,discovered decades ago,were re-examined with a fresh perspective and cutting-edge technology. Initial observations revealed previously undocumented carnivore tooth marks on both the upper jaw of the adult and the lower jaw of the juvenile. This prompted a deeper investigation.

AI to the Rescue: Identifying the Predators

To pinpoint the specific carnivores responsible for these marks, the researchers turned to the power of artificial intelligence. they employed computer vision – a branch of AI focused on interpreting images - to analyze the bite marks.

Hear’s how it worked:

- Training the AI: Deep learning models were trained on a vast database of bone markings created by modern carnivores like hyenas, crocodiles, and leopards.

- Blind Testing: The AI’s accuracy was rigorously tested in blind trials,where it had to identify the predator based solely on the bone markings.

- Remarkable Accuracy: The best-performing model achieved over 90% accuracy in identifying the animal responsible for the marks.

applying this sophisticated system to the H. habilis fossils overwhelmingly pointed to one predator: the leopard.

More Than Just Bites: Evidence of Consumption

The researchers didn’t stop at identifying the predator. They sought to determine why the leopards interacted with these H. habilis individuals. The evidence strongly suggests these weren’t just exploratory bites, but rather predatory attacks resulting in consumption.

Several key factors support this conclusion:

* Skeletal Fragmentation: The limited number of surviving skeletal fragments indicates meaningful scavenging and dismemberment.

* Leopard Feeding Habits: Leopards are primarily flesh-eaters. If another carnivore had already fed on the H. habilis remains, a leopard would likely have shown little interest.

* Mandibular Damage: The extensive damage to the lower jaw of OH 7 – including a fractured jawbone – indicates the leopard had to remove substantial amounts of flesh and tongue to access the interior. This points to active consumption, not simply a killing bite.

“We certainly know that to reach the inside of the mandible…a substantial amount of flesh and tongue had to be removed first,” explains Domínguez-Rodrigo. “This indicates consumption and not just a bite to kill.”

What This Means for Our Understanding of Human Evolution

This research offers a compelling new perspective on the challenges faced by early hominins.Homo habilis wasn’t just competing with other predators for resources; they were a resource.

This discovery highlights the vulnerability of our ancestors and underscores the importance of understanding the complex ecological pressures that shaped human evolution. It’s a stark reminder that the path to becoming human wasn’t just about developing tools and intelligence, but also about surviving in a world teeming with hazardous predators.

Image Credit: Vegara-Riquelme et al., 2025; CC BY-NC-ND 4.0