The Shifting Sands of Mars: How Atmospheric Pressure Rewrites the Story of the Red Planet’s Past

For decades,scientists have meticulously studied Martian landscapes,searching for clues about the planet’s past – a past perhaps harboring life. A key strategy has been to compare Martian features to similar formations on Earth, known as “earth analogs.” However, a groundbreaking new study from Georgia Tech, Arizona State University, the Open University, adn the Czech Academy of Sciences reveals a critical caveat: Mars’ drastically different atmospheric history fundamentally alters how water and sediment behave, rendering many Earth-based comparisons unreliable. This research, funded by NASA, isn’t just refining our understanding of Mars; its reshaping the very methodology of planetary geology.

The Atmospheric Pressure Problem: A Martian Reality Check

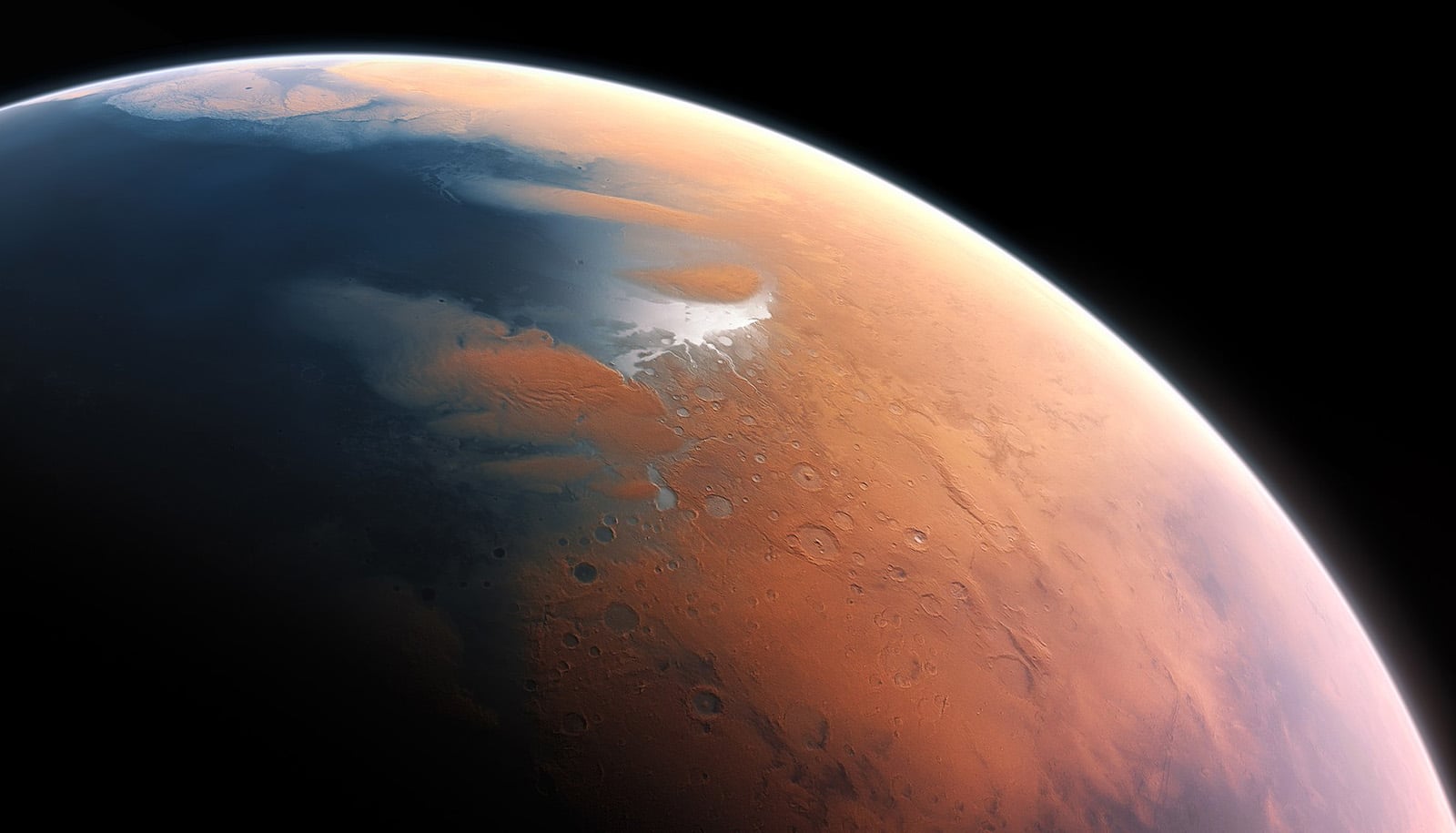

The core of the issue lies in atmospheric pressure. Earth’s relatively thick atmosphere exerts meaningful pressure, dictating how liquids and granular materials like mud interact. Mars,though,has lost much of its atmosphere over billions of years. This thinning atmosphere results in significantly lower pressures, creating conditions where familiar terrestrial processes behave in startlingly different ways.

“Earth’s thicker atmosphere means that ther are higher pressures on our planet, which produce very different behaviors,” explains Dr. Lujendra Ojha, a planetary scientist not directly involved in the study, but a leading expert in martian surface processes. “This research highlights the importance of considering thes basic differences when interpreting Martian landforms.”

The study, led by Jacob Adler (Arizona State University) and initially conducted during his postdoctoral work with Dr. Alejandra Rivera-Hernández at Georgia tech’s PLANETAS Lab, demonstrates that under low Martian pressures, water-sediment mixtures can either boil and levitate if warm, or freeze and flow like lava if cold. These behaviors are simply not observed on Earth. this means that features previously interpreted as formed by familiar Earth-based processes might have originated under entirely different, and far more exotic, conditions.

recreating Martian History in the Lab: A 70+ Experiment Deep Dive

To unravel these complexities, the research team meticulously recreated past Martian conditions within a specialized Mars simulation chamber.over 70 experiments were conducted, systematically varying pressure and temperature to observe the resulting flow dynamics of water-sediment mixtures.Sharissa Thompson, a PhD student at Georgia Tech and a key member of the PLANETAS Lab, played a crucial role in interpreting these results.

“As part of my PhD work, I uncover how and why flow shapes evolve as pressure changes,” Thompson explains. “This allowed us to understand how these flows could have shifted with changing pressures on Mars over time. The innovative flow experiments conducted in this study were a thrilling contribution.”

The results were revealing. At higher atmospheric pressures, prevalent in Mars’ early history (the Noachian period), the flow physics – known as rheology – of water and mud closely resembled that of Earth. This suggests that the oldest sedimentary features on Mars could indeed be comparable to those found on our planet, potentially indicating more habitable surface conditions in the distant past.

though, as Mars lost its atmosphere, the rules changed dramatically. The team found that at lower pressures, the rheology and resulting deposit shapes (morphology) became distinctly un-Earthlike. Furthermore, they discovered that these contrasting behaviors could occur simultaneously in different locations on Mars, driven by subtle variations in topography and local climate.

Implications for Martian Paleoclimate Reconstruction & future Exploration

This research has profound implications for our understanding of Martian history and the search for past life. By carefully analyzing the shapes of sediment flows, debris flows, and mudflows, scientists can now potentially estimate past climate conditions with greater accuracy.

“When we mapped out where on Mars we would expect this different behavior, we found that this opposite behavior could happen at the same time at different locations on the planet,” Adler shares. “The small-scale climate variations across Mars’ topography are enough to see these opposing effects.”

The study underscores the critical importance of laboratory experiments in planetary science. While remote sensing data and computer modeling are invaluable tools, they must be grounded in a fundamental understanding of how materials behave under planetary conditions.

“By finding matching morphologies of what we see on Mars and what we see in these lab experiments, we might be able to better time-stamp the paleoclimate record,” Adler explains. “We’ve sent rover missions to Mars largely because we find compelling remote sensing evidence of deposits formed by water or mud that could indicate a habitable environment. We are often eager to compare what we find to Earth analogs, but these are not always suitable for comparison. This study shows there is still much we can learn