The Brain’s Hidden Trick for Seeing What Isn’t There: How Illusory Contour Neurons Work

Have you ever looked at a picture and seen edges and shapes that aren’t actually drawn? That’s your brain at work, filling in the gaps and constructing a visual reality. Now, scientists are getting closer to understanding how your brain performs this remarkable feat, pinpointing a specific group of neurons responsible for perceiving illusory contours. This breakthrough could reshape our understanding of visual perception and potentially inform advancements in artificial intelligence.

Recent research, published in Nature Neuroscience (DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02055-5), has identified and functionally defined these “illusory contour encoder” (IC-encoder) neurons within the primary visual cortex. For years, scientists suspected their existence, but this study provides systematic evidence confirming they aren’t just rare anomalies – they’re a crucial component of how we perceive the world.

Decoding Illusory Contours: What Did the Study Find?

researchers, led by Shin and Adesnik, discovered that these IC-encoder neurons actively drive “pattern completion“ within the visual cortex.Essentially, they help your brain connect the dots, creating a complete image even when facts is missing.

Here’s a breakdown of the key findings:

* IC-encoders are a defined population: They aren’t scattered, random neurons, but a specific, identifiable group.

* Causal involvement in pattern completion: The study demonstrated that activating these neurons induces neural activity patterns mirroring those seen when perceiving real illusory contours.

* Neural depiction, not perception (yet): Importantly, the research focused on the neural activity itself, not whether the mice actually “saw” the illusions.

what are Illusory Contours?

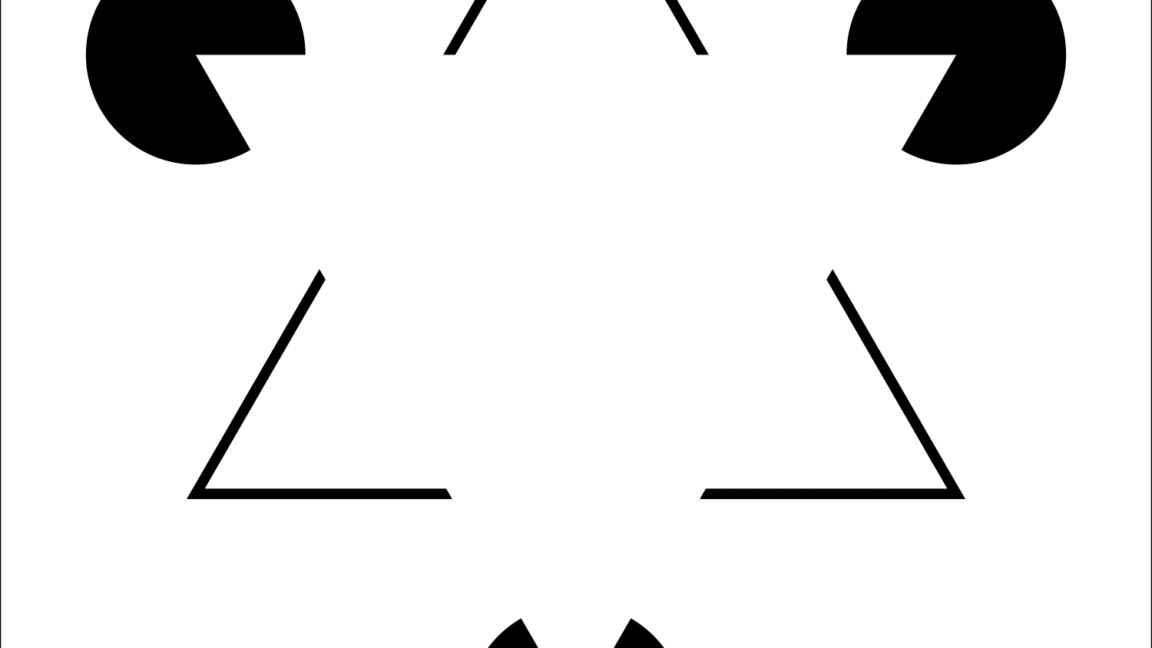

Illusory contours are visual perceptions of edges and shapes where no actual lines are present. Think of the classic Kanizsa triangle – you perceive a white triangle even though it’s formed by gaps in black circles. Your brain isn’t fooled; it’s actively constructing a more complete and meaningful representation of the visual scene.

The Next Steps: From Neural Activity to Behavioral Response

While this research is a significant leap forward, the question remains: do these activated neurons actually change what an animal sees? Currently, the answer is unknown. The study didn’t include behavioral tests.

Researchers are eager to move forward with experiments that will:

* Photo-stimulate IC-encoders: Artificially activate these neurons using optogenetics.

* Monitor behavioral responses: Observe if this activation leads to changes in the animal’s behavior, even without a visual stimulus.

* Increase neuron activation: Current technology limits the number of neurons that can be stimulated. Expanding this capacity is crucial.

“We’d definitely very much like to do this test,” says Adesnik. The challenge lies in the rarity and scattered distribution of IC-encoders, and the current limitations of optogenetic technology. Though, increasing the number of activated neurons could be the key to eliciting a measurable behavioral response.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding how the brain creates illusory contours has implications far beyond basic neuroscience.

* Insights into perception: It sheds light on the basic mechanisms of visual processing and how the brain constructs our reality.

* Artificial intelligence: Mimicking this process could lead to more refined AI systems capable of “seeing” and interpreting the world more like humans.

* Neurological disorders: Investigating these neurons could provide clues to understanding perceptual deficits in conditions like schizophrenia or autism.

Evergreen Insights: The Power of Predictive Processing

The discovery of IC-encoder neurons aligns with the broader theory of “predictive processing” in the brain. This theory suggests that your brain constantly generates predictions about the world and compares them to incoming sensory information.When there’s a mismatch, your brain adjusts its predictions – or, in the case of illusory contours, fills in the missing information to create a coherent perception. This isn’t a bug; it’s a feature. Your brain is actively trying to make sense of the world, even when the