#space #race #polluting #universe

Never before have there been so many emissions and waste from spacecraft and satellites in the Earth’s atmosphere. The cause: the spiraling space economy. And we will not fully understand the consequences of that increasing pollution until it is too late.

Shannon Hall / The New York Times3 februari 2024, 03:00

The high-altitude chase took place on February 17, 2023 over Cape Canaveral. SpaceX had launched its Falcon 9 rocket. Thomas Parent, a NASA research pilot, was flying a WB-57 jet when the rocket flew past his right wing. Stunned, he pushed his gear lever.

For about an hour, Parent dipped in and out of the plume of smoke in the rocket’s wake, while his colleague Tony Casey monitored the seventeen scientific instruments on board. Scientists hoped to use the data to show that they can analyze the smoke plume and ultimately understand the ecological effects of space launches.

In recent years, the number of launches has increased enormously. Commercial companies, such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, and government agencies are chasing thousands of satellites into low Earth orbit. And that’s just a start. In the long term, this could amount to a million satellites, and therefore many more launches, and therefore increasingly more emissions.

SpaceX declined to comment on the pollution caused by rockets and satellites. Amazon and Eutelsat OneWeb, two other companies envisioning mega-constellations of satellites, say they are committed to sustainability. Scientists, on the other hand, fear that the launches will release even more pollutants into the atmosphere. And it appears that regulators who assess the risks of space launches are not immediately inclined to issue rules to combat pollution.

Experts emphasize that they do not want to curtail the booming space economy. They do fear that the steady evolution of the sciences is slower than the current space race – in other words, we will not fully understand the consequences of pollution from rockets and spacecraft until it is too late. Studies already show that the upper atmosphere is full of metals from spacecraft, which disintegrate on their way back to Earth.

“We are changing the system very quickly, but our knowledge about those changes is not evolving at the same rate,” says Aaron Boley, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia and co-director of the Outer Space Institute. “We never really realize to what extent we are affecting our environment. And we do that again and again.”

Disruption

Before the rocket enters orbit, it has discharged two-thirds of its exhaust gases into the middle and upper layers of the atmosphere. Scientists expect them to sink downwards, to pack into the lower part of the middle layer of the atmosphere, the stratosphere.

The stratosphere houses the ozone layer, which protects us from the sun’s harmful radiation. But she is extremely vulnerable. Even the smallest change can have enormous effects on the ozone layer – and therefore also on the world below.

When the Pinatubo volcano in the Philippines erupted in 1991, so much sulfur dioxide was released into the stratosphere that the Earth cooled for years. The gas created a sulfate haze, which warmed the stratosphere while preventing the heat from reaching the Earth’s surface. Some scientists think that emissions from more and more rockets could have a similar effect on the climate.

At the moment, rocket emissions are insignificant compared to air traffic emissions. But scientists are concerned that even limited additional emissions into the stratosphere could have a much larger effect. Martin Ross, a scientist at The Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded research institute in Los Angeles, likens Earth’s atmosphere to a barrel of muddy water that has settled—mud on the bottom, relatively clear water on top. If you add more gunk to the muddy bottom, it won’t be immediately noticeable. If you add the gunk to the clear top layer, the water becomes cloudy or even muddy.

It is not known how the rockets will affect the relatively clear upper layer, the stratosphere. Scientists are concerned that black carbon, or soot, released during combustion processes in current rockets will have the effect of a continuous volcanic eruption. This disruption could deplete the ozone layer and have major consequences for the Earth.

In the 1990s, when space shuttles and other rockets were continually launched from American soil, studies predicted that the spacecraft would cause local ozone damage. One study predicted a 100 percent loss – which would create a small hole in the ozone layer over Cape Canaveral, allow ultraviolet radiation from the sun to reach Earth and lead to an increase in skin cancer, cataracts and immune system disorders.

The studies relied on models for the predictions, because there was no empirical data. Ross and his colleagues therefore began collecting data from high-altitude flights, which indeed found local ozone holes in the shuttles’ wake. However, those ozone holes recovered quickly and were not large enough to cause Cape Canaveral any problems – at least not at the frequency of launches at the time, about 25 per year.

But it is not said that this will also be the case in the future. In 2023, SpaceX single-handedly launched nearly a hundred rockets, mainly to build out its Starlink satellite network. This will soon be joined by Amazon, which plans to launch regularly for its Project Kuiper network, as well as other companies that want to be present in the space. The satellites provide many useful services, such as broadband connection anywhere on earth.

And it doesn’t stop once the thousands of satellites are on site. Many satellites have a lifespan of five to fifteen years, which means that companies must constantly send replacement devices into space.

Eropaf!

“I think we are now in a phase of the space industry that we had many decades ago with many developments on Earth,” said Tim Maclay, chief strategy officer at ClearSpace, a Swiss company that aims to do sustainable space development. “We see the possibilities, and then we rush into them without thinking much about the ecological consequences.”

A paper published in 2022 showed that the soot produced by rockets warms the atmosphere five hundred times more than soot from aircraft flying closer to the Earth’s surface. So that is the mud barrel effect.

“It means that as we start to develop the space industry and launch more rockets, we will see the effect increase very quickly,” said Eloise Marais, professor of physical geography at University College London and author of the study.

Another study, also published in 2022, found that if the speed at which rockets are launched were increased by a factor of 10, their emissions would lead to a temperature increase of 2 degrees Celsius in parts of the stratosphere. This would cause the ozone over most of North America, all of Europe and part of Asia to shrink. As a result, “people living at higher altitudes in the Northern Hemisphere would be exposed to more harmful ultraviolet radiation,” said the study’s lead author, Christopher Maloney of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences.

Little is known about the precise amount of soot emitted by the various rocket engines used. Most rockets use kerosene as fuel, which some experts say is “dirty” because it sends carbon dioxide, water vapor and soot straight into the atmosphere. But that may not be the dominant fuel in the future. For example, Starship, the launch system that SpaceX is developing, uses a mixture of liquid methane and liquid oxygen.

In any case, any hydrocarbon fuel uses some amount of soot. And even “green” liquid hydrogen rockets produce water vapor, which acts as a greenhouse gas at these dry high altitudes. “What is green in the troposphere is not necessarily green in the upper atmosphere,” says Boley. “There is no such thing as a completely neutral fuel.”

What goes up must sooner or later come down again. When the satellites in low Earth orbit reach the end of their life cycle, they break up into chunks through the atmosphere, leaving a stream of pollutants in their wake. Ross fears that the space industry’s biggest impact could be just that.

Gray zone

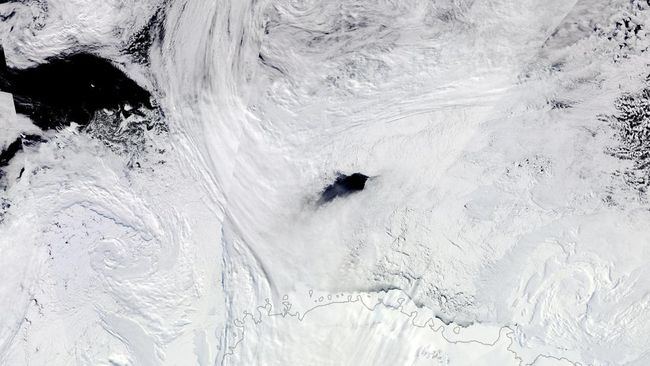

A study published in October 2023 reported that the stratosphere is already littered with metals from crashed spacecraft. Using the same NASA WB-57 that chased SpaceX’s rocket, scientists were able to explore the stratosphere over Alaska and much of the rest of the US. When they started analyzing the data, they saw particles that didn’t belong there. Niobium and hafnium, for example, do not occur naturally there, but are used in rocket boosters. These metals, as well as other elements clearly associated with space travel, were contained in about 10 percent of the most common particles in the stratosphere.

Boley, who was not involved in the research, assumes that this will only increase as humanity has only just begun the new satellite race. Although scientists are raising the alarm, they are not necessarily opposed to space companies or satellite operators. “We don’t want to shut down the space industry,” said Karen Rosenlof, a climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chemical Sciences Laboratory. According to her, satellites provide incredibly important services. They and others are calling for a regulatory framework to manage the ecological impact.

Rosenlof argues that there are ways to limit the impact of the space industry without shutting it down. Suppose scientists establish thresholds at which the industry begins to cause environmental damage when it exceeds them, then it may simply be enough to limit the number of launches and satellites. It is also possible to make improvements to the materials and fuels used.

Boley agrees. “There are many opportunities to protect the environment and do space travel at the same time,” he says. “We just need to get a good look at the bigger picture.”

But to succeed, scientists say, satellite operators and rocket companies need rules. Currently there are hardly any.

“Space travel thrives in a gray zone,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. “She falls between the folds of all regulatory authorities.”

The Montreal Protocol, for example, is a treaty that successfully sets limits on the use of chemicals that damage the ozone layer. But it says nothing about rocket emissions or satellites. In the US, the Federal Communications Commission licenses large satellite constellations, but does not consider the potential harmful effects on the environment. And the Federal Aviation Administration estimates the ecological impact of rocket launches on Earth, but not in the atmosphere or space.

‘Limit impact’

Is the future of the stratosphere thus in the hands of Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and other space company owners and executives? Boley is very concerned about this, because the space industry has no desire to slow down. “Unless it has direct financial consequences for the companies, they don’t care. For them, the environmental damage is nothing more than an annoying inconvenience.”

A spokesperson for telecom company OneWeb, which has launched more than 600 satellites, says it is committed to sustainability in satellite design, constellation planning and launches. “We work closely with public and private partners to minimize environmental impact,” said Katie Dowd, a director at the company.

Nevertheless, OneWeb wants to expand its presence to approximately seven thousand satellites.

© The New York Times