2026-01-16 02:47:00

Inuit flags, clockwise from upper left: Nunavut, Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), Nunatsiav, Invialuit, and Nunavik

7 November was International Inuit Day (Inuktitut: ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᑉᓗᐊᓂ) and, back then. I got to wondering what, if any, presence Inuit have had in Los Angeles. I didn’t have anything ready for publication on that date, though, so I set it aside. But in the aftermath of our regime’s attack on Venezuela in order to ̶s̶t̶o̶p̶ ̶t̶h̶e̶ ̶f̶l̶o̶o̶d̶ ̶o̶f̶ ̶f̶e̶n̶t̶a̶n̶y̶l̶ ̶f̶r̶o̶m̶ ̶a̶n̶d̶ ̶r̶e̶s̶t̶o̶r̶e̶ ̶d̶e̶m̶o̶c̶r̶a̶c̶y̶ ̶t̶o̶ take its oil, talk has again turned back to Greenland, which is apparently as integral to the US’s security as Taiwan is to China‘s, Ukraine is to Russia‘s, or Palestine is to Israel‘s. I though, given its importance to our growing empire, t I’d use the renewed attention to examine the connections between its native Inuit population and Los Angeles. If Greenland becomes a territory or protectorate of Greater America, roughly 32% of the world’s Inuit will suddenly lose their access to free universal healthcare, free university education, federal voting rights, federal benefits, and constitutional status. You’re welcom!

The singular form of the plural, Inuit, is Inuk. Inuit are often divided, into four geopolitical groups: Alaskan Iñupiat, Canadian Inuit, Greenlandic Inuit, and the Yup’ik (also spelled Yupik) of Alaska and Russia. Those large groups can be further divided into distinct, smaller groups including the Cup’ik, Inughuit, Inuinnait, Inuvialuit, Kalaallit, Kivallirmiut, Naukan, Netsilingmiut, Nunamiut, Nunatsiavummiut, and Tunumiit. In 1977, the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) was formed to represent Indigenous peoples across the Arctic. The ICC officially, then, adopted Inuit as an inclusive term for all of these related people in order to create a more powerful collective voice within environmental policy discussions and international law. The Inuit homeland is known as Inuit Nunaat.

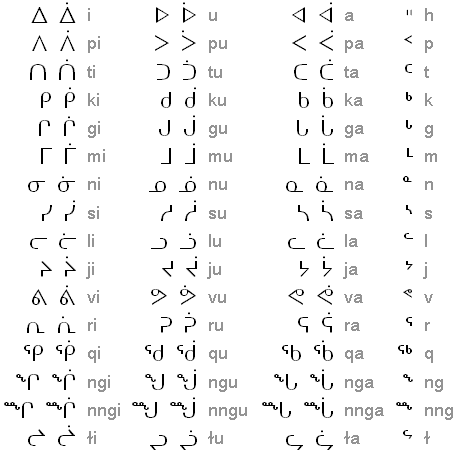

Before the ICC, the Inuit (along with other northern peoples including the Unangan (indigenous Aleutians) and the Chukchi of Chukotka were often referred to by the exonym “Eskimo.” Today, especially in Greenland and Canada, this is widely rejected as, at best, antiquated and, at worst, inappropriate. However, it apparently remains a comparatively common self-identification within Russia and the US’s Inuit communities. Meanwhile, the language family that contains Inuit languages — Inuktut or Inuktitut — is usually referred to as Eskimo–Aleut Language, “Eskaleut,” or, less problematically (but less elegantly, too), Inuit-Yupik-Unangan. Inuktut is usually written in one of three alphabets: Cyrillic in Russia, Roman orthography (Latin alphabet) in the rest of Inuit Nunaat, or Inuktitut syllabics (based on Canadian Aboriginal syllabics).

A CONDENSED HISTORY OF THE INUIT

The ancestors of the modern Inuit are believed to have split from the related Unangan and other circumpolar peoples around 2000 BCE, when the Earth was undergoing a period of significant climatic and geographic transition toward cooler and more arid conditions.

A distinct culture developed in the region of the Bering Strait around 1000 CE, when farming and pastoralism were increasingly common in warmer parts of the world — but when the hunter-gatherer life was still dominant in the north. These people were first labeled “Thule” by Danish archaeologist Therkel Mathiassen in the 1920s. The term comes from ancient Greek and Roman literature, where Ultima Thule is the name of the mythical land at the farthest northern edge of the world. The Thule were the ancestors of the Inuit.That’s the era in which ᐊᑕᓈᕐᔪᐊᑦ (Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner) is set. It’s one of my favorite films.

THE INUIT AND THE TUNIIT

In their homeland, these people thrived — aided by their advanced technologies, including large boats skin boats called umiaks, dog sleds, bow and arrow, toggling harpoons, and quasi-subterranean houses made of whale bones and sod called qarmat. From there, they spread east. First they displaced the Tuniit, a socially avoidant people who’d lived in isolation for 4,000 years and who lacked the Inuit’s dog sleds, umiaks, bow and arrow, and advanced whaling technology. Centuries earlier, they’d had bow and arrows, actually, but apparently lost or abandoned the technology. They rarely, if ever, mixed with their neighbors, who included the Innu along the Labrador Coast, and the Norse, who’d lived in southern Greenland since roughly 986.

In Inuit accounts, the Tuniit were gentle giants who, although they lacked the Inuit’s transportation, hunting, and building technologies — were large and capable of lifting massive boulders — but also shy and easily frightened. Interestingly, Inuit accounts don’t recount more than minor conflicts between the two people and DNA suggests virtually no genetic intermixing. The Tuniit seem to have died out, for the most part, on their own. Their decline began around 1300 CE and was complete by roughly 1500. They left behind their own technologies which the Inuit adopted — including soapstone lamps, distinct harpoon tips, cold iron forging (using meteoric iron), and spun yarn fiber.

THE INUIT AND THEIR SOUTHERN NEIGHBORS

In the South, the Inuit encountered people like the Dene,Iinuuch, Iiyiyuuch, Innu, Maskêkowiyiniwak, Nêhinawak, and Nīhithawak. They had lived in what’s now Canada, by then, for at least 10,000 years and were highly-specialized forest-dwellers. The tundra, presumably, held little appeal for these people of the forest — except when caribou migrated north into it. The borders of their homelands corresponded closely with the tree line of the the subarctic boreal forest. The Inuit established trade networks with them — but conflicts were frequent between the people who’d lived in the region for millennia and the Inuit.

THE INUIT AND THE NORSE

The Norse had first visited Greenland around 982, when Erik the Red was banished from Iceland for manslaughter. He established the first European colony in North America about four years later. Interactions between the Norse, in southern Greenland, and the Tuniit in the far north, were infrequent. When the Norse arrived, they found Tuniit ruins and the region had been abandoned. The two people sporadically encountered one another when hunting walruses. Trade between the two people, apparently, was rare.

Norse accounts of the Inuit, however, (who the Norse referred to as Skrælings) portray a more complex set of interactions between the two peoples. In the mid-1300s, priest Ívar Bárðarson wrote that he encountered feral cattle wandering amongst the ruins of a decimated settlement. An Icelandic account from 1379 records a specific attack where eighteen Norse men were killed and two boys were taken as slaves. The Norse, who the Inuit knew as Kavdlunait, describe an initially peaceful coexistence. Sites such as Sandhavn feature ruins of both Inuit winter houses and Norse farms side-by-side. Inuit tales, though, tell of a “lying maid” named Navaranaq, who apparently stirred up conflict between the two people’s she lived amongst. Ultimately, though, it seems that it was nature, not the Inuit, who brought about the end of the Norse’s first North American settlement. Rising sea levels flooded Norse pastures, the walrus ivory trade collapsed as elephant ivory became more accessible, and a prolonged drought that caused the starvation of Norse cattle. With the Tuniit and Norse gone, the Inuit were Greenland’s sole inhabitants…. and about half a century later, a Genoese explorer “discovered” North America when he landed in the Bahamas, which he believed was Japan.

INUIT NUNAAT DURING THE IMPERIAL AGE

Following the disappearance of the Tuniit and Norse, the Inuit were the sole inhabitants of the North American High Arctic — but that would, of course, change. In Inuit Nunaat’s east, the English and Danish explorers made their way to Greenland in the 1570s; and Dutch and British whalers began trading with Inuit in the late 1600s. Norwegian Hans Egede established a mission and trading post near modern-day Nuuk in 1721, which began the colonization of that land.

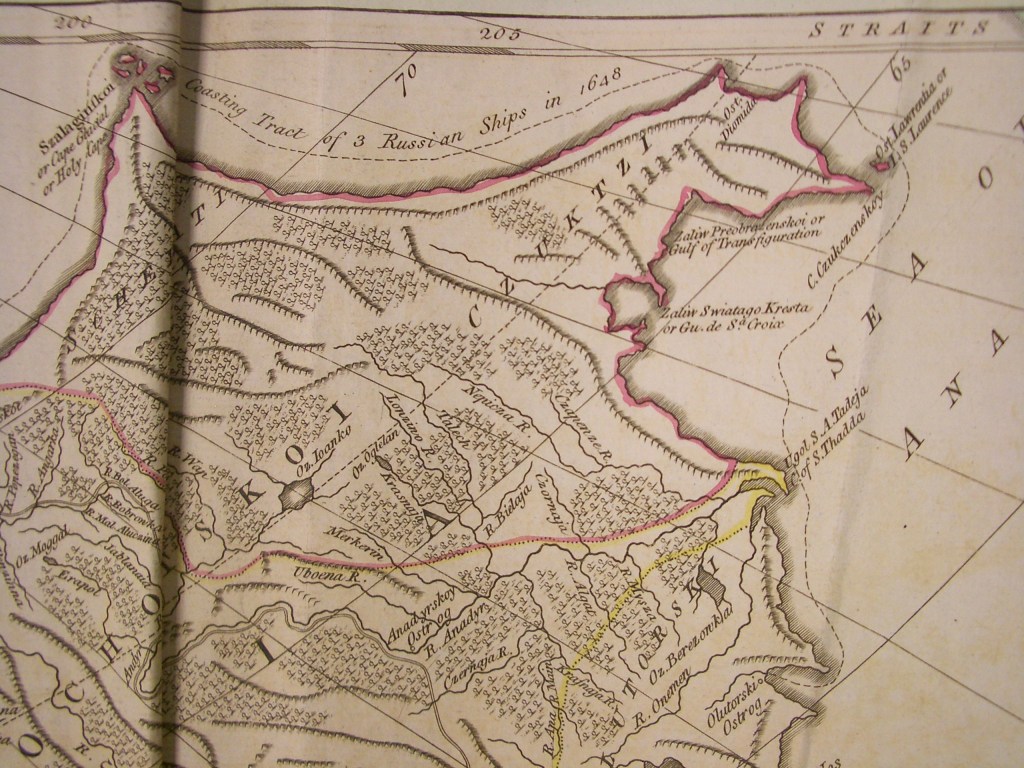

In Inuit Nunaat’s west, the Cossacks, led by Semyon Dezhnev, arrived in Chukotka in 1648. The Russians traded marine mammal products, using the Chukchi and Koryak as middle-men, with the Inuit. The Chukchi, however, maintained a fierce resistance to colonization and Russia gave up trying to conquer them and finally signed a peace treaty in 1778. Meanwhile, Russia made first landfall in Alaska in 1741. There the warred with and enslaved the Alutiiq and Tlingit. Disease, too, decimated Alaska’s indegenous people. Russian Orthodox missionaries developed a written Yup’ik languae using the Cyrillic alphabet and established churches and schools. Alaska was sold the the US in 1867 and became a state in 1959.

In Inuit Nunaat’s south, the Hudson Bay Company (HBC), established by the French in 1670, began providing guns to the Inuit’s southern neighbors in order to prevent them from interacting directly with the fur-trading British, in order to protect their dominance in the fur trade. In 1771, Moravian missionaries arrived from what’s now Czechia armed with Inuktitut translations of the Bible. That same year, a party led by Matonabbee ambushed Kogluktogmiut camp which led to roughly twenty being massacred for which a healing ceremony was undertaken in 1996. Canada purchased Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the HBC in 1870. Britain transferred the remaining Arctic islands to Canada via the Adjacent Territories Order in 1880. Active federal governance did not begin in earnest until 1921. By the 1950s, the Canadian government intensified its presence through forced relocations and assimilation policies (e.g. residential schools) to solidify their control.

Today, Inuit Nunaat is no longer under complete unilateral control, but is administered by four nations: Canada, Denmark, Russia, and the USA. Greenland (known in Greenlandic as Kalaallit Nunaat) is an autonomous territory. within the Kingdom of Denmark. Greenland became an autonomous territory in 1979, following a referendum that established Home Rule. This status was further expanded on June 21, 2009, through the Act on Greenland Self-Government.

Roughly 43% of Inuit live in Canada, where Nunavut, Nunatsiavut, Nunavik, and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region all enjoy various degrees of sovereignty. Nunavik gained significant administrative autonomy following the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) signed in 1975 and establishing the Kativik Regional Government. The Inuvialuit Settlement Region was stablished in 1984 with the signing of the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA); providing the Inuvialuit with specific rights over land, resources, and wildlife management. Nunavut was formally established as a distinct territory in 1999, following the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993). Nunatsiavut became an autonomous region in 2005, when its constitution was ratified and the Nunatsiavut Government was established.

Roughly 15% of Inuit live in Alaska, where the Iñupiat and Yup’ik exercise some self-determination through Alaska Native Regional Corporations and the tribal governments established under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Finally, about one percent of Inuit (Yup’ik) live in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, a federal subject of Russia created for the indigenous Chukchi but also home to various other North Asian peoples, including the Chuvans, Evens, Kereks, Koryaks, and Yukaghirs.

INUIT CALIFORNIANS AND ANGELENOS

Today, California, is home to the third-largest population of Alaska Natives in the US (after Alaska and Washington) – although that figure encompasses a diverse range of roughly a dozen distinct peoples, including not just the Inuit but also the non-Inuit Alaska Athabascan, Eyak, Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Unangax̂. Los Angeles, meanwhile, is home to the largest urban population of American Indians and Alaska Natives — a census term that inludes anyone and everyone with “origins in any of the original peoples of North, Central, and South America” from the Inuit homelands in the north all the way over to the Yaghan of Chile’s subantarctic Navarino Island in the south. Someone should, by the way, tell the writers at the census that Central America is part of North America. Imagine if there was a umbrella census category that encompassed all the people’s of the Eastern Hemisphere. It makes finding any specific demography information about Inuit, specifically, in either California or Los Angeles rather challenging. Luckily, I’ve found a few Inuit Angelenos who’ve contrbuted to the metropolises history and culture.

COLUMBIA ENEUTSEAK

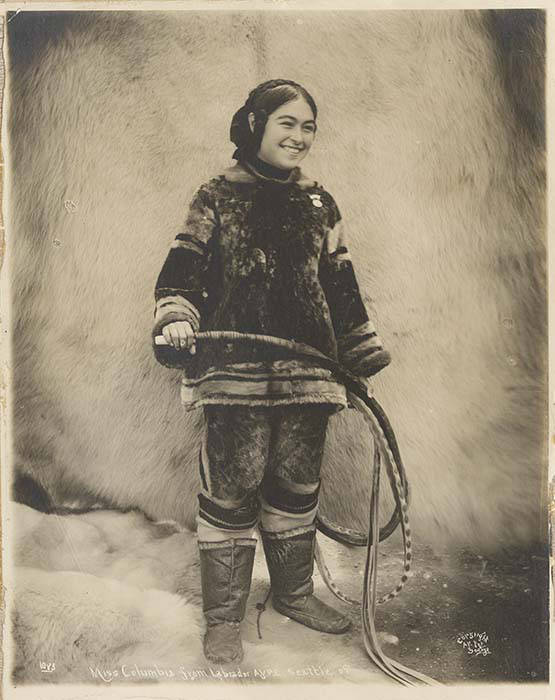

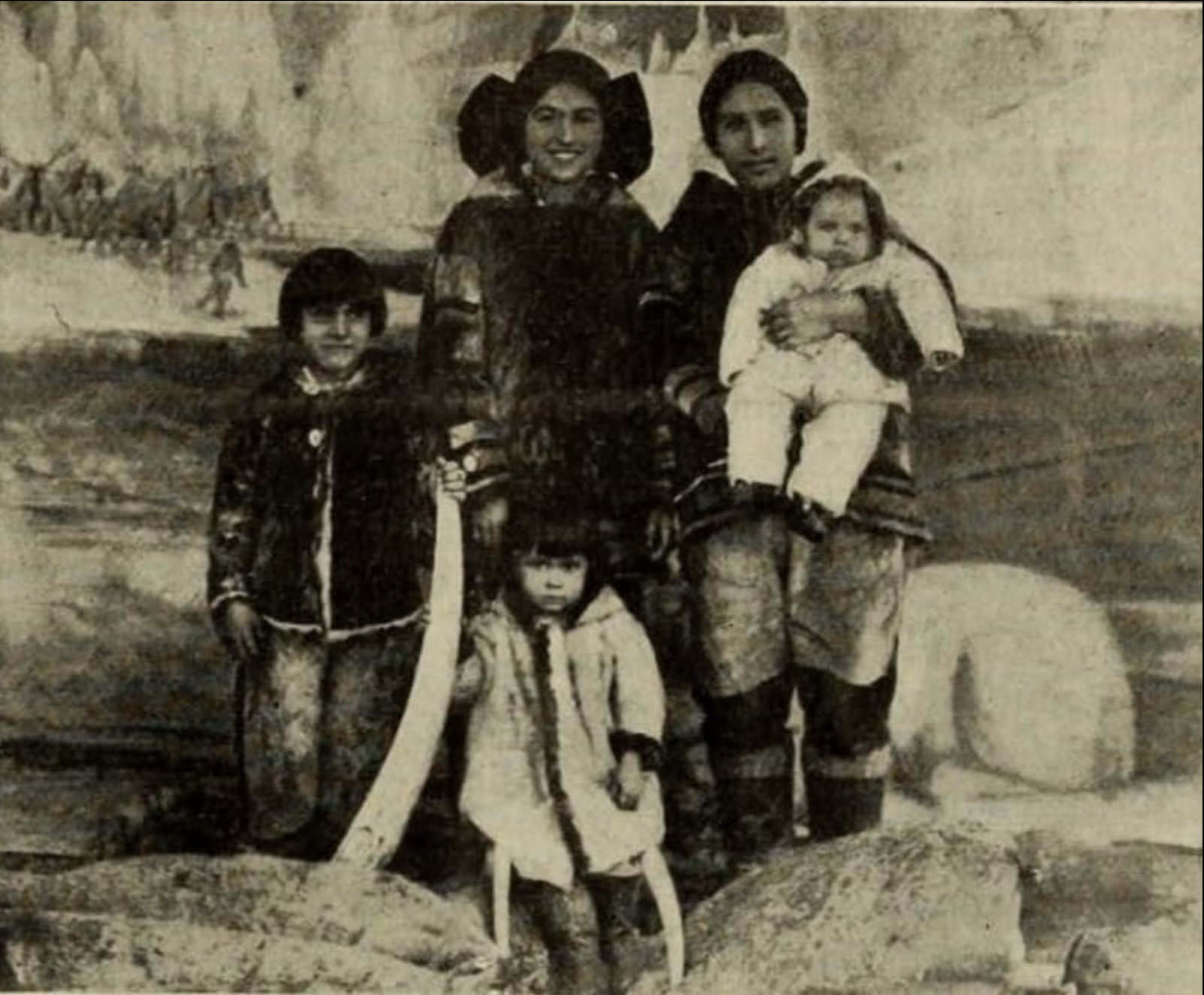

Columbia Eneutseak and promotion from The Way of the Eskimo depecting the actress with with her siblings and mother, Esther, 1911

Columbia Eneutseak (also known as Nancy Columbia) was born on 16 January 1893 at the the World’s Columbian Exposition (commonly known as the Chicago World’s Fair). Her family were from Labrador (ᓄᓇᑦᓱᐊᒃ) and had travelled to Chicago to appear in the expo’s “Eskimo Village” ethnographic exhibit. Her given name was bestowed to her from the head of the exposition’s Board of Lady Managers, Bertha Matilde Palmer. As a child, she went on to appear in other expositions, with the Barnum & Bailey and Ringling Bros. circuses, and at Coney Island. She returned to Labrador in 1896 and remained there, with her grandparents, until 1899, when she rejoined her parents on a tour of England, France, Italy, Spain, and North Africa.

When she was sixteen, Eneutseak was voted “Queen of the Pay Streak” at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition in Seattle. Afterward, she began a career as an actress in film. In 1911, she appeared in five films. The Way of the Eskimo (1911), a Northern by the Selig Polyscope Company in Edendale (now Silver Lake), was the first film to feature a professional Inuk actor and was based on an original story Eneuteak had written herself. It also featured her mother, Esther Eneusteak. 1911’s other films were Lost in the Arctic, The Eskimo Orphan, The Witch of the Everglades, and The Seminole’s Sacrifice. She went on to appear as an actress in God’s Country and the Woman (1916), The Flame of the Yukon (1917), and The Last of the Mohicans (1920).

Eneutseak was joined in Los Angeles by her mother, stepfather, and four siblings. They established an “Eskimo Village” attraction on the city’s Ocean Park Pier in Santa Monica, which opened in 1910. At least five other Alaskans also appeared at the village, including a trio billed as Doc Sam (aka Samuel Doc and Samuel Dock), Kauvechka (son of Kauvechka and Neunauk), and Selalok (daughter of Aballoak and Neutsiak). The village was managed by Captain John C. Smith, the stepfather of Nancy and husband of her mother. There, they sold fur rugs and skins, wolf and dog teams, and “everything to make up a good show or Arctic Picture.” Kauvechka and Selalok were married at the Ocean Park Dance Pavilion that August. A fire destroyed the pier (and Eskimo village) in December 1915. In the 1920s, Eneutseak married projectionist Raymond S. Melling. In 1927, they had a daughter, Esther Sue Melling, after which Eneutseak transitioned into a career as an apartment manager. Eneutseak had a stroke in 1948. She died in 1959.

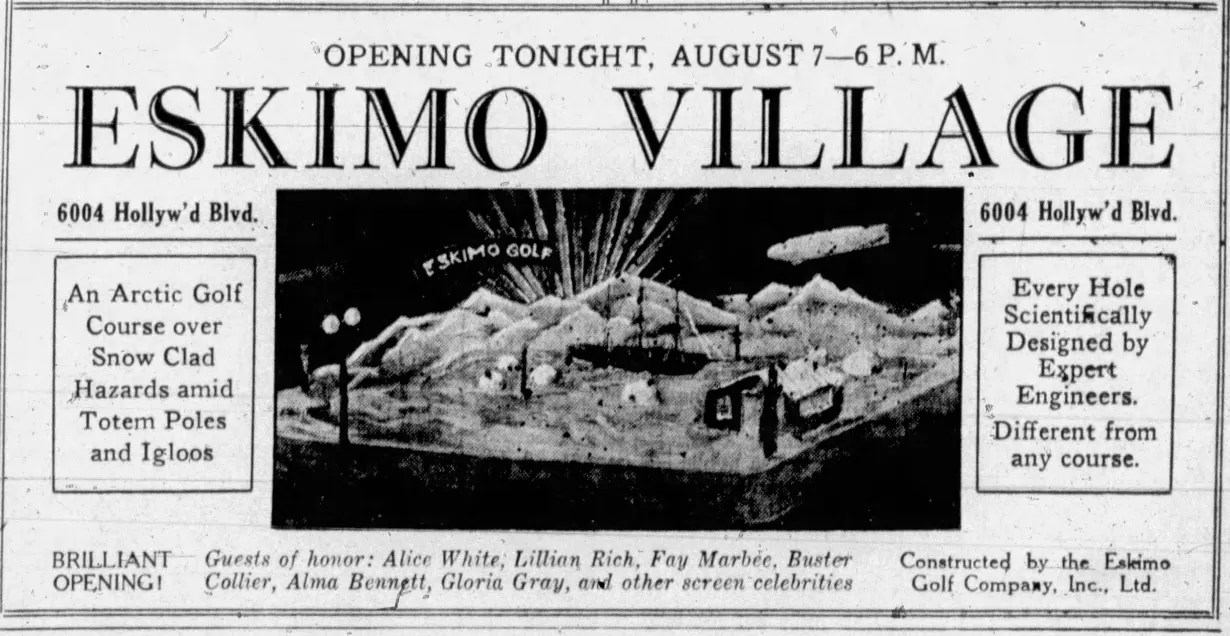

ESKIMO VILLAGE MINIATURE GOLF COURSE

An Inuit-themed miniature golf course, Eskimo Village, opened at 6004 Hollywood Boulevard in August 1930. That year, during the height of the miniature golf craze, there were reportedly 300 miniature golf courses in Hollywood alone – likely an exaggeration as that would translate to more than twenty every half-square mile. If nothing else, opening an Arctic themed putt-putt during a Los Angeles summer exemplifies a typically Angeleno disinterest in logic or authenticity that has always fuelled the region’s kitsch culture. Eskimo village featured icebergs, igloos, totem poles, and shipwrecks. It was organized by film director Sid Algier and designed by H.C. Lydecker, a former art director and miniatures expert for the Tiffany-Stahl studio. Algier intended for it to be the first in a chain of such courses. Sadly, it lasted only one season and it was converted into a used car lot.

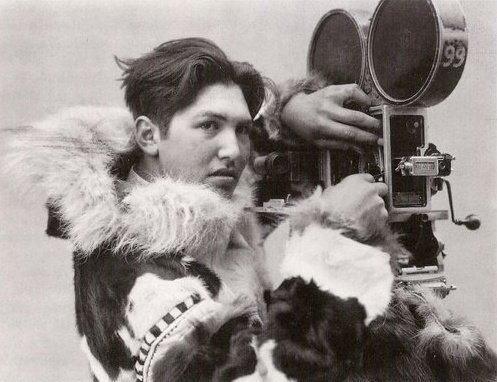

RAY MALA

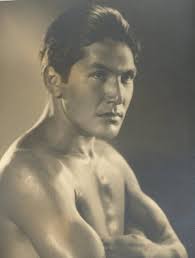

The first Alaska Native Hollywood star was Ray Mala. He was born Ray Agnaqsiaq Wise to a Russian Jewish father (Bill Wise) and Iñupiat mother named Karenak Ellen “Casina” Armstrong – English family names were then bestowed by various Christian mission schools and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. His father was a fur trader and Ray was primarily raised by his Inuit maternal grandmother, Nancy Armstrong.

Ray Wise made his film debut in Alaska, at the age of fourteen, in which he had a minor acting role and served as an assistant cameraman on Primitive Love (1921). Between 1921 and 1924, he worked as a cameraman for Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen during his “Great Sled Journey” in which he documented Inuit songs and stories. Wise moved to Los Angeles in 1925 and lived in an apartment in the Beachwood Canyon neighborhood. In 1926, he worked as an assistant camera operator for the Fox Film Corporation, on the documentary, Primitive Love. In 1932, he was briefly married to an Inuit woman, Gertrude Becker.

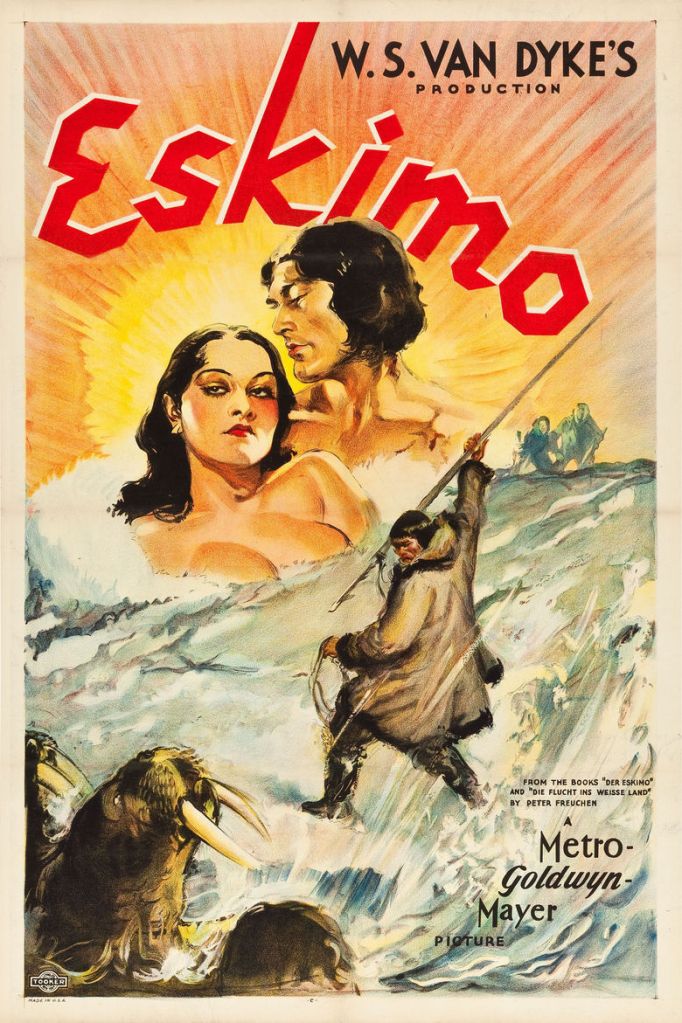

In 1933, Wise starred as Mala in the film, Eskimo, for which he adopted Mala as his stage and family name. It was the first Hollywood film to be shot almost entirely in the far North and featured a largely Inuit cast speaking Inuktitut. After its massive success of Eskimo, Mala had a string of major starring roles in films, including Last of the Pagans (1935), The Jungle Princess (1936), and Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island (1936). Around 1937, Mala moved to a no-longer-extant home in West Adams. He married Galina Kropotkin Liss.

With the implementation of the Hayes Code, roles for Latin Lovers, Lotus Blossoms, Noble Savages, &c began to dry up and, increasingly, white actors in racial makeup (blackface, brownface, redface, and yellowface) were employed to skirt anti-miscegenation restrictions while still depicting “exotic” romances. In 1946, Ray and Galina gave birth to their son, Theodore “Ted” Mala. After a series of smaller, supporting roles, Mala shifted his primary focus back to working as a cinematographer and cameraman on films including Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Laura (1944), The Fan (1949), and Les Misérables (1952). In 1952, he returned to acting for Red Snow, a Cold War-era thriller set in Alaska – and filmed at Hal Roach Studios in Culver City. In it, Mala played the Inuit sidekick, Sgt. Koovuk, to Guy Madison‘s US Air Force pilot character. Lt. Phil Johnson. On 23 September 1952, at the age of 45, Mala suffered a fatal heart attack on set. He was interred at Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery. Galina died on 2 July, 1953, at the age of 44.

The orphaned Ted was sent to an Irish Catholic boarding school but eventually graduated from Harvard University with a focus on medicine and public health. In 1975, he moved to Alaska to practice medicine and served as Commissioner of Health and Social Services from 1990-1993. After retiring in 2015, he began a three-year effort to secure permissions and funding to move the remains of his parents from Hollywood Forever to Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery.

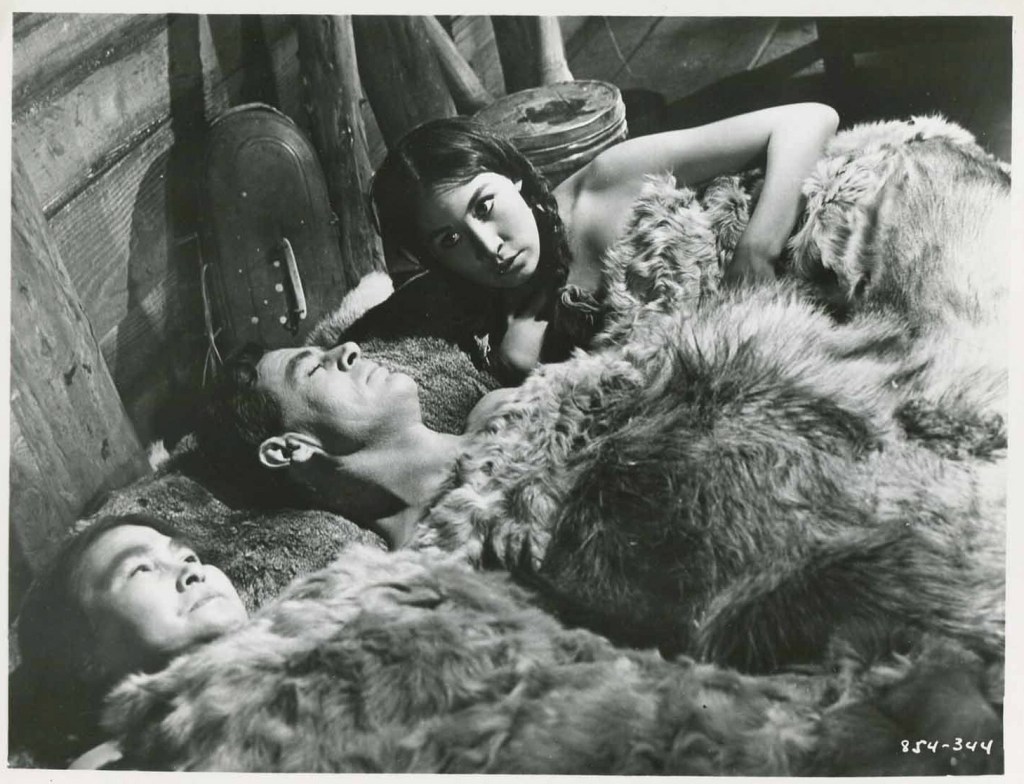

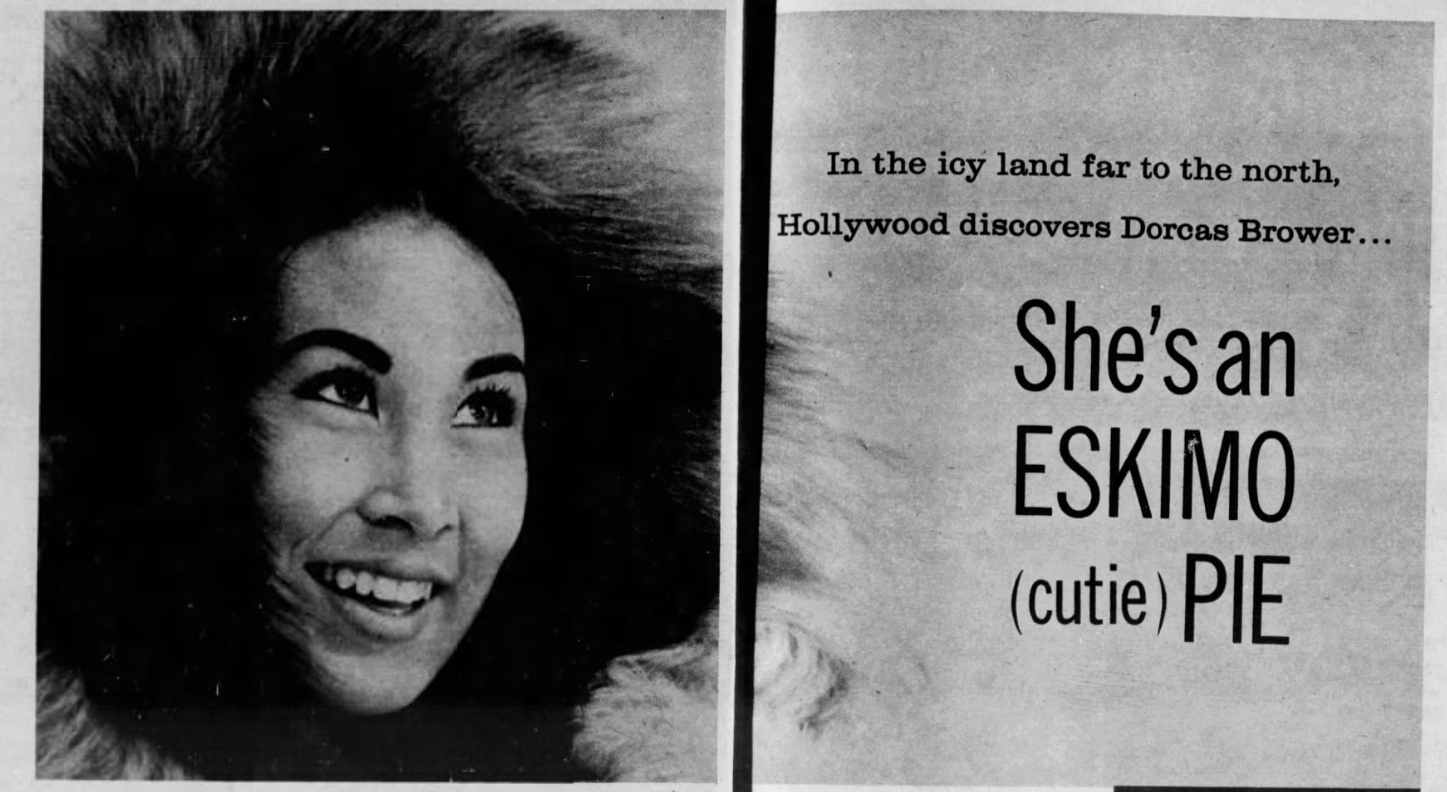

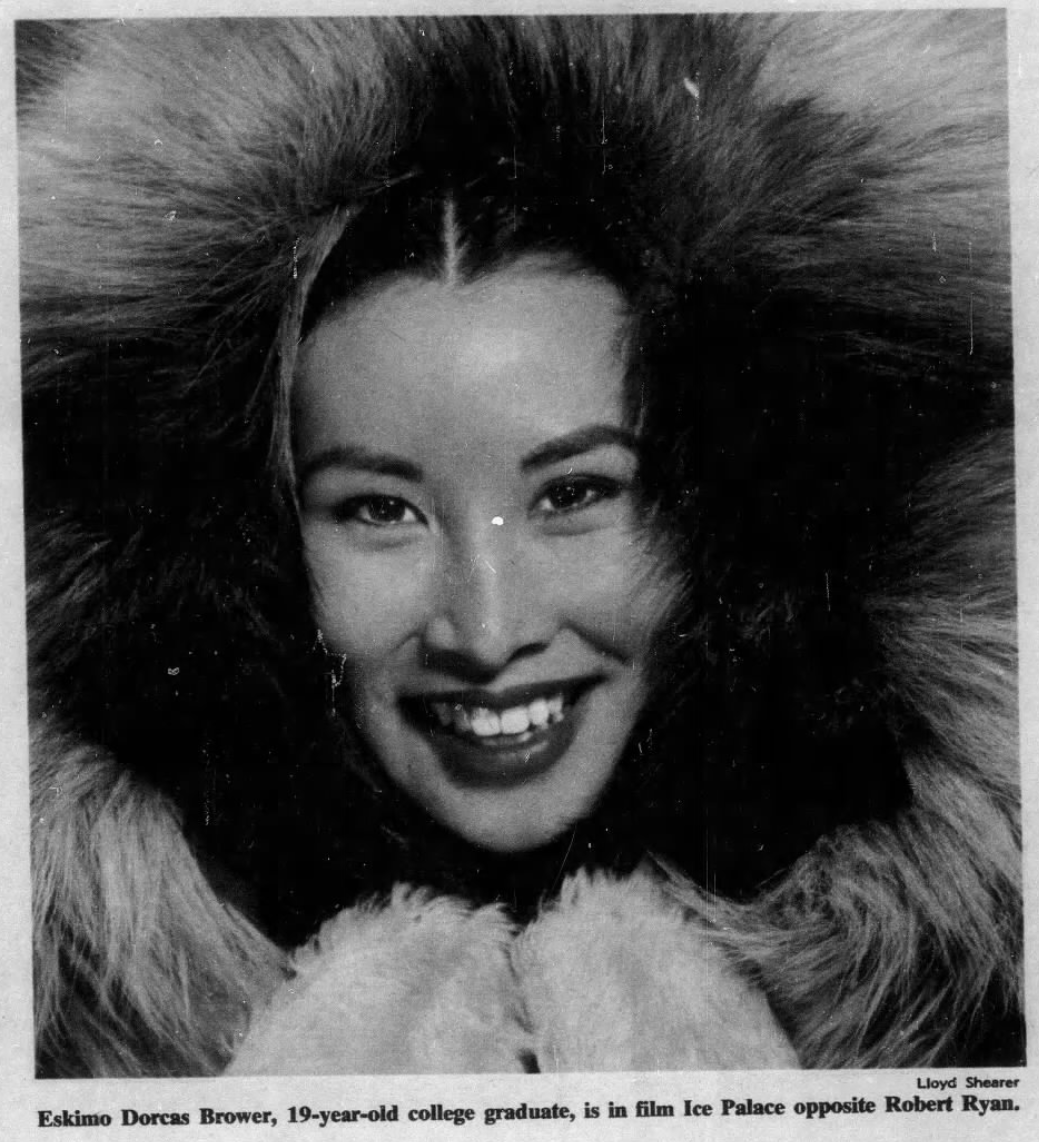

DORCAS BROWER

Iñupiaq actress Dorcas Brower achieved international fame as “Una” in the 1960 film, Ice Palace. She was born in 1940 in Utqiaġvik (Point Barrow) to Emily Qaummagun Hopson and Charles “Charlie” Brower Jr. The Browers are a prominent family in the region. Dorcas’s grandfather, Charles Brower, was a famous American trader who married an Inuk woman named Asianggataq. Dorcas’s aunt, Sadie Brower Neakok, was the first female magistrate in Alaska.

Brower was studying dramatics as a student at Sheldon Jackson Junior College in Sitka, Alaska, when she was discovered by talent scouts who wanted an Inuk actress for the sake of authenticity. Some scenes were filmed on location in Juneau, Petersburg, and Fairbanks – but principal filming took place in Burbank, on sets. Whereas Mala was cultivated as a star, Brower was treated more like a cultural ambassador. She was even said, falsely, to have been Miss Alaska. During the film’s promotion, Drawer spoke lovingly of Southern California’s weather and unfavorably of the blizzards of her homeland. Brower likely stayed in studio-arranged housing or a local hotel near Warner Bros. and – after her obligations were completed, she returned to Alaska where she became a flight attendant and later went on to co-found a regional airline, Cape Smythe Air Services.

Dorcas Brower married Grant B. Thompson Sr. on 23 June 1961. She gave birth to Grant B. Thompson Jr. Unlike his mother, he came to Hollywood to work and remained, penning screenplays (McFarland, USA (2015)) and producing (The Hating Game (2021). Dorcas Brower died in 2017.

THE WHITE DAWN

The White Dawn (1974) was a high-profile Hollywood production distributed by Paramount Pictures. It was the first major Hollywood film to be shot entirely on location in the Canadian Arctic, specifically on Baffin Island near Iqaluit. It starred Warren Oates, Timothy Bottoms, and Louis Gossett Jr. – three established Hollywood actors – but was notable for using an almost entirely local Inuit cast of non-professional actors who spoke Inuktitut on screen.

MALAYA QAUNRIQ CHAPMAN

Malaya Qaunirq Chapman was born in Iqaluit around 1988 and raised in Pangnirtung, Nunavut. After her mother and grandmother died, she was brought to Los Angeles as an eleven-year-old by her adoptive mother, filmmaker Lori Stoll, which served as the inspiration for the 2016 film Heaven’s Floor (filmed in Los Angeles and Nunavut and starring Katie May Anawak-Dunford).

She returned toIqaluit and the documentary series, including Illinniq (2010-2017) and won the Miss Nunavut title in 2011. She starred in the sketch show, Qanurli (2011-2017), Entwined (2014), and Restless River (2019) – and also established a career as a journalist for APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network). She currently hosts the cooking show, Nunavummi Mamarijavut (2018-present).

AMANDLA STENBERG

Actor and activist Amandla Stenberg was born in Los Angeles in 1998. Her paternal grandmother, Ena Stenberg, is a Greenlandic Inuk radio personality and singer who moved to Denmark. Amandla Stermberg began her career as a four-year-old model for Disney before appearing as an actress in films including The Hunger Games (2012) and The Hate U Give (2018).

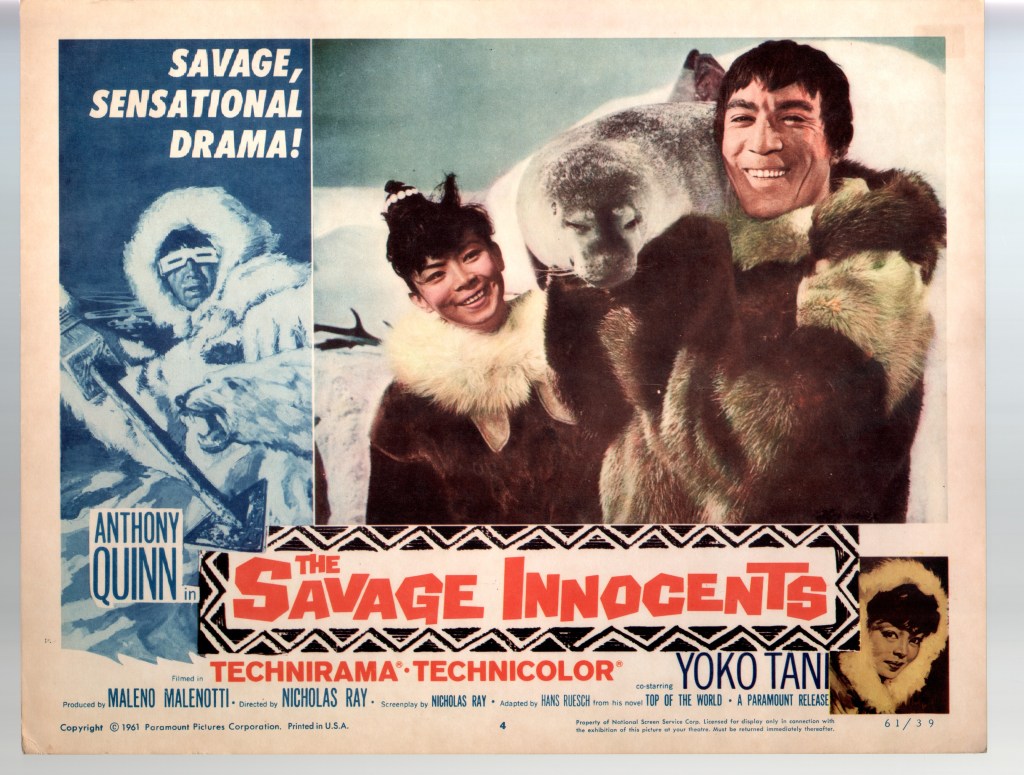

Historically, Hollywood never made much effort to cast Inuit in Inuk roles for the most part. Ray Mala’s wife, in Eskimo, was played by Japanese-Hawaiian, Lotus Long. Anglo-American Mala Powers played an Alaska Native in 1951’s The Wild Blue Yonder. Irish-Mexican Anthony Quinn started in the 1960 film, The Savage Innocents. His wife was played from French-Japanese Yoko Tani.

Today, though, when Hollywood occasionally ventures up north, such as with True Detective: Night Country (2024), they’re more likely to feature Inuit actors in Inuit roles. Meanwhile, two Inuit producers, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril and Stacey Aglok MacDonald (who co-founded Red Marrow Media in 2019) have been increasingly involved in Hollywood, and helping to further shift the gaze. So far, they’ae most recognized for co-creating the 2025 series, North of North (originally known as Ice Cove), Netflix’s first scripted series filmed in Canada. Nowadays if a series takes place in an Inuit setting, it’s more likely to feature Inuit talent – such as (in the case of these two series) Aka Niviâna, Angunnguaq Larsen, Anna Lambe, Keira Belle Cooper, Kelly William, Maika Harper, Malaya Qaunirq Chapman, Nivi Pedersen, Nutaaq Doreen Simmonds, Phillip Blanchett, Tanya Tagaq, Vinnie Karetak, and Zorga Qaunaq.

INUIT MUSIC

Of those Inuit actors, Amandla Sternberg, Phillip Blanchett and Tanya Tagaq are also musicians. Yup’ik/Inuit brothers Phillip and Stephen Blanchett are in an Inuit soul band, Pamyua, and throat singer, Tagaq, has performed in Los Angeles on several occasions, including with the Kronos Quartet at Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2008 (her Los Angeles debut), at Grand Performances in 2009, and at the Broad in 2016.

Sisters Jamie and Jenny Christensen are Iñupiaq pop musicians who moved from Utqiaġvik to Los Angeles in 2011 to pursue professional careers in the music industry as the duo, Jamie and Jenny. They have their own recording studio in Carson.

INUIT ART IN LOS ANGELES

Inuit art comes from a creative tradition rooted, traditionally, in mythology and, historically, has used materials like serpentine stone, walrus ivory, and whalebone. It’s known for its streamlined, “lyrical organicism.” I’m not aware of any local Inuit artists nor of any galleries dedicated primarily to Inuit art. However, there are and have been rotating exhibitions at major institutions like the Autry Museum of the American West, which currently features Arctic perspectives in its “Future Imaginaries: Indigenous Art, Fashion, and Technology” exhibition (on view through June 2026).

The Fowler Museum sometimes integrates Inuit works into its global ethnographic displays, and LACMA holds Arctic pieces that are occasionally rotated into thematic displays of Indigenous American art.Contemporary Inuit voices are showcased in the city through specialized galleries and events, such as the photography of Anchorage-based Iñupiaq photographer, Brian Adams at LA Artcore.

COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS

Several organizations in Los Angeles serve the broader American Indian and Alaska Native communities, including the United American Indian Involvement, the Southern California Indian Center, and the American Indian Community Council. No specifically Inuit organizations, as far as I know, exist here.

FURTHER READING

Taissumani, a column by Kenn Harper

Support Eric Brightwell on Patreon

Eric Brightwell is an adventurer, essayist, rambler, explorer, cartographer, and guerrilla gardener who is always open to paid writing, speaking, traveling, and art opportunities. He is not interested in generating advertorials, cranking out clickbait, or laboring away in a listicle mill “for exposure.”

Brightwell has written for Angels Walk LA, Amoeblog, Boom: A Journal of California, diaCRITICS, Hey Freelancer!, Hidden Los Angeles, and KCET Departures. His art has been featured by the American Institute of Architects, the Architecture & Design Museum, the Craft Contemporary, Form Follows Function, the Los Angeles County Store, Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, Skid Row Housing Trust, the 1650 Gallery, and Abundant Housing LA.

Brightwell has been featured as subject and/or guest in The Los Angeles Times, VICE, Huffington Post, Los Angeles Magazine, LAist, CurbedLA, LA Times 404, Marketplace, Office Hours Live, L.A. Untangled, Spectrum News, Eastsider LA, Boing Boing, Los Angeles, I’m Yours, Notebook on Cities and Culture, the Silver Lake History Collective, KCRW‘s Which Way, LA?, All Valley Everything, Hear in LA, KPCC‘s How to LA, at Emerson College, and at the University of Southern California. He is the co-host of the podcast, Nobody Drives in LA.

Brightwell has written a haiku-inspired guidebook, Los Angeles Neighborhoods — From Academy Hill to Zamperini Field and All Points Between; and a self-guided walking tour of Silver Lake covering architecture, history, and culture, titled Silver Lake Walks. If you’re an interested literary agent or publisher, please out. You may also follow on Bluesky, Duolingo, Facebook, Goodreads, iNaturalist, Instagram, Letterboxd, Medium, Mubi, Substack, Threads, and TikTok.