the Master Clock Unveiled: How a Small Network of “Hub” Cells Orchestrates Our Daily Rhythm

For decades, scientists have known the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain is the central pacemaker of our circadian rhythm – the roughly 24-hour cycle governing sleep, hormone release, body temperature, and countless other physiological processes.But how this tiny structure, containing roughly 20,000 neurons, manages to coordinate such a complex system, ensuring our bodies stay synchronized with the external world, has remained a profound mystery. Now, a groundbreaking study from Washington University in St. Louis is providing an unprecedented map of the SCN’s intricate communication network, revealing that a surprisingly small number of “hub” cells are critical for maintaining this vital synchrony. This discovery, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, not only deepens our understanding of basic biological timing but also opens exciting new avenues for treating sleep disorders, seasonal affective disorder, and the health challenges faced by shift workers.

Beyond Static Maps: A Dynamic View of Circadian Communication

Previous research has focused on the anatomical connections within the SCN – essentially, a static wiring diagram. However, the brain isn’t a collection of fixed circuits; it’s a dynamic network where communication flows and changes over time. To capture this dynamic interplay, researchers led by Professor Erik Herzog and research scientist KL Nikhil developed a novel computational tool called MITE (Mutual Data and Transfer Entropy).

“MITE captures cellular connections by studying how signals flow between cells, moving us beyond static anatomical maps to study functional communication in living tissue,” explains Nikhil. This innovative approach allowed the team, a truly interdisciplinary collaboration spanning biology, electrical engineering, and chemistry, to reconstruct over 25 million connections among 8,000 cells across 17 mice with remarkable accuracy (over 95%).

The Hub-and-Spoke Model of Circadian Timekeeping

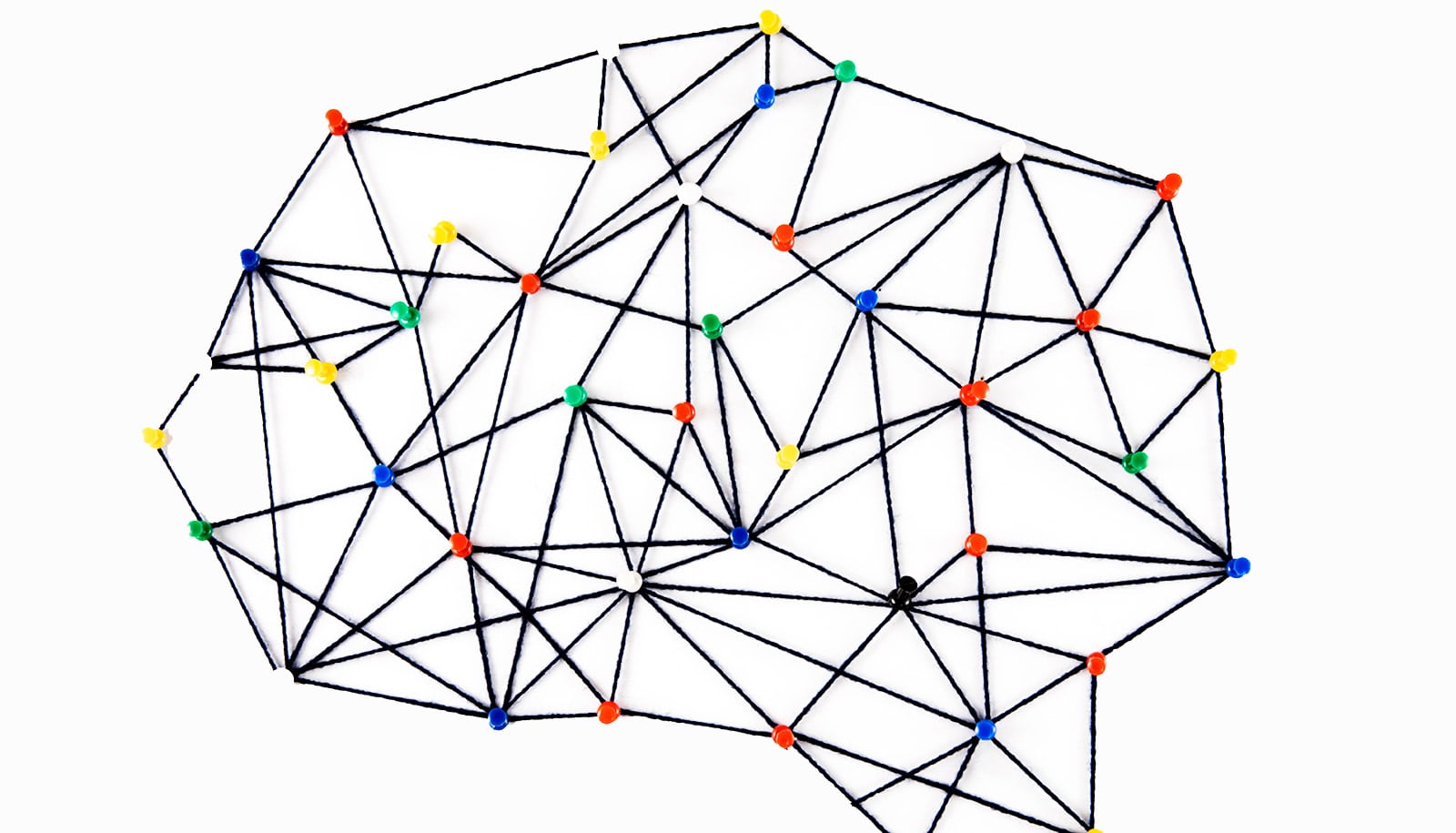

The resulting network map revealed a surprising organizational principle: not all SCN neurons are created equal. The SCN operates on a “hub-and-spoke” model, where a small subset of highly connected neurons act as central coordinators.

“Think of these connections like airplane routes; we mapped the pathways to understand which SCN cells communicate with each other. We reasoned that major hubs direct traffic and represent points of vulnerability,” Nikhil elaborates.

Further analysis identified five distinct functional cell types,defined not just by the molecules thay express (like neuropeptides) but,crucially,by who they communicate with. The team confirmed the established role of neurons expressing vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) in synchronizing the SCN, but went further, discovering that an even smaller subset of VIP-expressing neurons act as super-hubs, generating and broadcasting signals that maintain network-wide synchrony.

These VIP hubs don’t operate in isolation. The research identified “bridge” cells that relay signals from the hubs, and “sink” cells that receive these signals, ultimately conveying timing information to the rest of the body. This hierarchical structure highlights the importance of communication patterns in defining cellular function. as Nikhil succinctly puts it, “It turns out that it is not just what a cell expresses, but who it communicates with, that defines its function in the network.”

Validating the Hub Model and Future Therapeutic implications

To confirm the critical role of these hub neurons,the researchers built computational models of the SCN network. Simulations demonstrated that removing only the hub neurons led to a complete collapse of synchrony, powerfully supporting the idea that these cells are essential for maintaining accurate timekeeping.

This discovery has significant implications for developing targeted therapies for a range of conditions. The team is now focused on understanding how these hub cells exert their influence and exploring whether targeted interventions can “tune” SCN timing. This could lead to neuroengineering strategies to realign the body clock in individuals suffering from:

* Shift Work Disorder: Disruptions to the circadian rhythm caused by irregular work schedules.

* Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): Mood changes linked to seasonal variations in daylight.

* Sleep Disorders: Including insomnia and other conditions affecting sleep quality.

* Jet Lag: The temporary disruption of the circadian rhythm caused by rapid travel across time zones.

“With this approach,” Nikhil states, “we can begin to understand how clock wiring differs between ‘morning’ and ‘evening’ individuals, across seasons, and how it becomes disrupted by shift work or rapid travel across time zones.”

A New Era in Circadian Biology

The Washington University team’s work represents a major leap forward in